I found forgiveness while working with the very people I had grown up condemning

This blog continues “‘Les Miserables: Finding God in the theatre (Pt. 1).”

Experiencing Grace

MY OWN INDIFFERENCE to the problem of AIDS was brought to light when I performed in a reading of Larry Kramer’s play, The Normal Heart, here on our small island during the World Aids Day festivities.

The show tells the story of the outbreak of the AIDS epidemic, told through the eyes of a reluctant activist who eventually throws his life into the cause of finding a cure.

I first found out about the opportunity when Dr. Stephen Floyd, the drama director at the high school where I teach, reached out to me at lunch. He was sitting beside me at the crowded table of teachers when he spoke.

“You might want to audition,” he suggested quietly. “I think they need men.”

They did. Except for the female doctor and the director, the cast was entirely male. Almost every actor was also gay. I was cast as the brother of the protagonist, the one who refuses to support his sibling — he cannot see the growing scope of the AIDS epidemic.

During one of the introductory exercises, I sat amidst the cast, growing more and more uncomfortable as I realized that all my peers in this cast had been very aware of the epidemic, with many of them actively fighting to raise public and governmental awareness throughout the 80s. It was an existential problem for them. They had watched friends around them sicken and die. They could have died.

And where was the evangelical church?

Nowhere helpful. In fact, many of the Christians with whom I had associated myself in that decade had ignored or actively resisted offering help.

The most vocal screamed about God’s hatred for homosexuals, the damnation they deserved. And by saying nothing within the evangelical church, I was party to those statements. By Jesus’ own words, I stood condemned.

I had chosen the wrong side.

“I hated you.”

As the introductions continued around the circle, I made a crucial decision. When it was my turn, I took a deep breath.

“Like my character, I ignored this problem. In the 1980s, I was part of the fundamentalist, evangelical community that condemned gays, who showed no empathy at all for those dying of AIDS.”

I suppose I could have clarified that some in the evangelical community did show empathy and compassion. But that night, I couldn’t think of any.

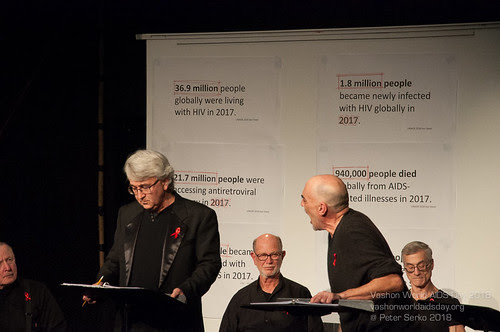

The cast of The Normal Heart stands on stage just before the performance begins. The staged reading completed the four-day arts festival, which acknowledged and commemorated those lost to AIDS on Vashon Island WA. Courtesy of Peter Serko

My stomach tightened, and I flushed as I looked around me. Almost all of them had lost dear friends in the epidemic that had raged across our country, an epidemic that was invisible to me and my friends during my young adult years.

“You did a good job of casting me,” I said, turning to our director.

There were murmurs of support from my new friends. Some of them were surprised by my confession. None of them condemned me in return.

And at that moment, I sensed grace — the grace that I had failed to offer the gay community during the worst period of their history. In fact, I sensed forgiveness. I didn’t need to worry that they might find out what kind of person I was back then.

They knew the worst.

Now I could be honest with this group of friends, some new and some old. I didn’t have to hide who I was.

Several days after the reading, I ran into one of the audience members. He was a tall, thin man. I was talking to a friend at Minglement, a coffeehouse here on the island, and he approached me.

He complimented me on my performance. Then ironically, he added one stipulation.

“I hated you during the reading, though.”

Steven Denlinger performs across from island actor Chris Boscia in The Normal Heart at the Open Space for the Arts on Vashon Island on December 2, 2018. Courtesy of Peter Serko

I didn’t blame him. My character — are older brothers always this dense? — didn’t have any idea that his indifference is far worse than hate. Not until the end, when he and his brother find redemption in their relationship.

It was a powerful moment for me as I played it on stage.

Although I was just supposed to be acting, in reality, it felt as real for me as it was for the two brothers within that scene.

Another moment of grace.

A Perfect Analogy

Is it any wonder that so many have turned away from the church? And therefore, from a God promoted by such an organization?

Jean Valjean, the escaped convict in pre-revolutionary France, is a perfect analogy of the way a religious society treats those condemned by an unjust legal system. According to the gospel of Christ, Christians are commanded to give to those in need — with no judgment attached.

The story of Fantine within Les Miserables mirrors Valjean’s story: a young woman who struggles on the outskirts of polite society. Episode 2 of this mini-series has just been released on PBS. Photo courtesy of dailymail.co.uk

This is not the reaction Valjean gets. He is refused shelter by normal people. But he is taken in by a bishop. When Valjean flees in the dead of the night with his host’s silverware, he is arrested. But the bishop surprises him by telling the police the silverware was a gift. Then the bishop loads up Valjean’s arms with two more silver candlesticks.

But my friend, you left so early

Surely something slipped your mind

You forgot I gave these also

Would you leave the best behind?

There is no condemnation in the bishop’s actions. No judgment. Only empathy and kindness.

Listening to the music of this scene invariably brings me to tears.

Questioning my lack of Grace

Today, when I reflect back on my choices, I wonder. I see the way the characters in Les Miserables respond. I see the power of their choices. Why couldn’t I have responded with the same grace, the same lack of judgment, when my gay friends in the theatre told me their stories?

Why did I remain passive — silently buying the evangelical response that God was punishing the gay community with the AIDS epidemic?

I knew better.

I had seen God in a rogue bishop who lies to the French policemen in order to confront Valjean with the grace of Christ. I had seen the bishop lay claim to Valjean’s soul. Why could I not have understood then how to become a vehicle of grace in transforming the lives of those who find no grace within the evangelical church?

Why was this epidemic not an existential crisis for me, as well?

But at that point, I was still as blind as the rest of the evangelical community.

I was Inspector Javert.

Seeing the show a second time

I remember clearly the second time I went to see Les Miz. By then, I had the musical almost memorized, thanks to the cassette tapes I purchased and played on my Walkman. I often fell asleep in my dorm room at Richmond College, listening to it.

So when a friend came to see me in London, we decided to pay for good seats. This time, instead of sitting in the nosebleed section, I was sitting five seats from the front.

The themes of freedom and justice and poverty are lifted straight from the gospel message of Christ in Victor Hugo’s original novel Les Miserables. Photo courtesy of Evening Standard

I knew the story by then. I knew the music by heart. I knew what to expect.

But I couldn’t have been ready. Not for that. Not for the reality that I would begin crying during the scene with the bishop, unable to stop. To my surprise, my friend was also sobbing.

I’ve never had that experience while watching a show, before or since. Afterwards, my friend and I went out for burgers, and we talked about what we had experienced.

We didn’t understand how we — two young men still in college — could still be wiping tears over burgers and fries and chocolate milkshakes. We just knew we had seen a show we would never forget.

I knew at that point that I would not be returning to the strictures of the evangelical Christian world. I knew I didn’t agree with the sense of judgment that world offered those who disagreed.

I just knew I needed to find a faith that purveyed the Grace of Valjean rather than the Judgment of Javert.

Les Miserables as a Soul Teacher

IT IS FOR this reason that I consider the musical Les Miserables — written by Victor Hugo and adapted for the stage by the librettist Herbert Kretzmer — to be a Soul Teacher.

No other story or musical can still make me cry every time as I listen to it, literally 30 years later. Within this musical, I see the pure gospel of Christ at work. I find a reason to respond with openness and tolerance, rather than judgment and hatred towards those I don’t understand.

Today, as I look across a world where Grace is becoming more and more absent in the evangelical church, I long for congregations of faith where being right about correct doctrine takes a backseat to being right about how we respond to those who need our help — whether they be our gay brothers and sisters, or the homeless people increasingly crowding our streets, or illegal immigrants begging for shelter at our borders.

And so, back at my home church on Passion Sunday — as I looked into June’s open, vulnerable, trusting eyes — I placed a small piece of the broken bread in her hand, and I spoke the words that matter so much to a person of faith.

“The body of Christ.”I

If you like what you are reading, please follow our Soul Teachers website and “Like” us on Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn. Or you can reach me at StevenDenlinger@thesoulteachers.com. The first six episodes of our Soul Teachers podcast, which I host, are in post-production and will soon begin airing weekly.

Leave a Reply