Moment of Grace

This past Sunday morning, I found myself doing something I’ve never done before. Proffering the bread in communion to each person kneeling at the communion rail — saying the words The Body of Christ — and looking them directly in the eyes.

Communion bread and wine. Photo courtesy of Patheos

I had never fulfilled this role before. I was worried before I started. I thought, for example, that I’d have to serve them the wine — and with my luck, I’d spill the blood of Christ all over someone’s lap.

It was a horrifying thought, whether or not you believe the wine is the actual blood, or the presence of Christ is in the wine, or the wine is just a symbol.

Fortunately, I was permitted to just serve the bread.

As I approached each person, I looked them directly in the eyes, and said with great gravitas, “The body of Christ,” picking out each piece of manufactured, transformed bread and putting it into their hands.

But the real shock was something I had never considered.

For those who raised their eyes to meet mine, I saw something I had only experienced in myself, eyes that were filled with emotion and faith and trust and belief.

I remember handing the bread to one woman, June, a committed believer who ensures that snacks are offered to everyone in our Coffee Hour after church each day. She is in her eighth decade. She is kind, thoughtful, complimentary. As I looked her in the eyes, placing the bread in her palm, in that moment, everything stopped for me.

True Faith

I believe true faith transforms a person.

I remember watching Les Miserables in London, shortly after I had arrived for my year abroad on a Rotary scholarship.

Steven poses on a theatre trip to ancient Greece during his year abroad in London as a Rotary Foundation Scholar in March 1989. Photo courtesy of Steven Denlinger

I had determined to see as many plays and musicals as I could, and by the end of September, I had gotten one of the cheap seats — in the nosebleed section of the Palace Theatre, so far up the figures on stage looked like tiny dolls.

But even that far away, the story was still riveting.

The moment in which I was swept away occurred toward the beginning. Jean Valjean, after spending 19 years at hard labor in prison, has just been released by the sadistic Inspector Javert, who warns him he’ll be watching.

At first, Valjean tries to follow the rules. We know by then his original crime was stealing a loaf of bread to feed his starving family. But as he is turned away by people who only see a criminal in front of them, he finally grows desperate, bitter, and angry.

The image used to advertise the musical. Photo courtesy of Amazon.com

When a bishop invites him in and feeds him, he takes advantage of the man’s generosity, fleeing in the middle of the night with some silver candlesticks. Of course he is caught and dragged back to the bishop by policemen who chortle to him about his dank future. But to his surprise, the bishop lies to save him from prison.

He asks Valjean in front of the arresting officers why he would “leave the best behind,” loading up Valjean’s arms with more silver candlesticks — it’s a fortune Valjean has now received.

Set free, alone on the streets, Valjean doesn’t know how to react. He realizes clearly the bishop could have condemned him to a life sentence in prison. Instead, he ensures that Valjean goes free.

I feel my shame inside me like a knife

He told me that I have a soul

How does he know?

What spirit comes to move my life?

Is there another way to go?

I found myself leaning forward, tears, real tears, rolling down my cheeks.

Moment of Transformation

I was in a worldly theatre thousands of miles away from my community of faith, and here was a Catholic bishop — and I had been taught across 12 years of parochial Conservative Mennonite schooling that the Catholics had burned my ancestors for refusing to baptize babies or worship Mary — who was acting like Christ.

But it was the words of the bishop that told me everything.

But remember this, my brother

See in this some higher plan

You must use this precious silver

To become an honest man

By the witness of the martyrs

By the passion and the blood

God has raised you out of darkness

I have bought your soul for God.

The actions of a believer had changed the way Valjean saw the world and himself.

Ministers of Satan

It was not the first time I had heard the music of Claude-Michel Schönberg. I had seen and heard it on a high school stage several months previous, and it was just as moving.

The previous May, having finished my student teaching at Hoover High School in North Canton, Ohio, I was looking to secure a job there after I graduated with my teaching certificate. In my quest to secure an eventual job, I had attended the spring choir festival in May with my cooperating teacher.

By then, I was anxious to see my students again. I missed them.

The music was mostly straight out of the 1950s. But there were a few modern pieces — toward the end of the evening, the choir’s elite ensemble took the stage. They began a medley of songs from Les Miserables. High schools all over America were singing this medley since the show had opened at the Broadway Theatre on March 12, 1987, two years before.

Now in front of me the stage lights dimmed and one of the students I had taught, a young woman in a white peasant blouse and brown skirt, moved into the bright spotlight.

I dreamed a dream in time gone by

When hope was high and life worth living

I dreamed that love would never die …

At first, I marveled at my student’s voice, and then suddenly, she wasn’t my student any more. She was a French peasant girl whose life had gone wrong, who had lost every trace of hope.

But I was young and unafraid,

And dreams were made and used and wasted

There was no ransom to be paid,

No song unsung, no wine untasted …

I was there in the streets of Paris, listening to this girl — someone who just needed help. I found myself in tears.

The musical Les Miserables was released as a film by Universal in 2012. It was directed by Tom Hooper, written by William Nicholson, and starring Hugh Jackman, Russell Crowe, and Anne Hathaway. Photo courtesy of National Catholic Reporter

The theatre had become for me another vehicle of Grace.

This made no sense to me, especially since I had been taught from childhood that the theatre was evil, that those who went to it were on the world’s path to damnation, and that actors were ministers of Satan.

By the time I had arrived in London for my Rotary Foundation Scholarship, I had begun to doubt those who had taught me this from childhood.

I had also begun to understand what the musical adaptation of Victor Hugo’s epic novel about the poor was all about.

Message of Grace

By the time I arrived in London in August 1988, I had entertained dreams of directing theatre, and especially writing original theatre.

So after I saw the show in the West End, I began researching its origins. I saw the message of Christ’s gospel told clearly: that grace could transform a hardened criminal, and people who refuse that grace experience damnation.

So how could a den of iniquity produce such a clear message of grace?

I had always been taught by my father that theatre was created by actors — a word that in Greek meant “hypocrite.”

I remembered my uncle Joe Overholt, a sort of misfit in our community who was both scholarly and deeply pietistic, who stood up and thundered short sermons direct from God himself, about the evils of theatre, about how the original Greek interchanged the words hypocrite and actor.

I was especially fascinated by Les Miserable’s creation — developed for two years by the Royal Shakespeare Company. Against all odds, the show almost didn’t happen.

It had been funded by the Royal Shakespeare Company in Stratford. The producers had fired the original librettist at the last minute because his script was too dense, the lyrics virtually unmusical. Once the show was up and running, they planned to transfer it to the Barbican in London.

But the producers had doubts.

At one point in 1985 — when previews were at their worst, when critics were tearing apart the show’s future — the producers decided to cancel it. But when they called from Stratford to London, trying to reach the ticket office, they discovered the entire run of the show had sold out. They wanted to extend it.

Most of all, the story of its creation astonished me. How could people who were damned — actors who led loose, unregenerate lives — create a show whose themes of faith reached to the deepest parts of my soul?

Yet here was theatre preaching the salvation story. Here were actors — hypocrites — telling the gospel story.

I couldn’t understand it.

Meeting God

It was around that time that I read about the first time Colm Wilkinson performed “Bring Him Home” during the show’s first table reading.

Colm Wilkinson performs the music of Les Miserables. Courtesy of Playbill.com

It’s at the moment when Valjean realizes that his adopted daughter loves a boy — a young fighter for the resistance in Paris — and the boy is in great danger. The father has gone out to find and rescue him.

God on high, hear my prayer

In my need, you have always been there

He is young, he’s afraid…

“It was like hearing the voice of God,” an actor present for that table reading said.

I thought the reaction was sacrilegious.

The voice of God in theatre? Grace found in the theatre? For a conservative Mennonite trying to come to grips with his attraction to drama, that was a conundrum.

The directors and actors I knew by then in London didn’t seem to have much faith.

My first experience acting in a play was there in London in the American college I was attending. The theatre was led by an actor/director who questioned my faith, telling stories about his own loss of faith, doing his best to break me down.

Today, I know how stiff I must have been then, how self-absorbed I was with my own journey to manhood, how difficult it must have been for the cast to work with me. He was merely trying to help me find my own authentic voice.

I was anything but authentic.

At the end of August 2017, a group of Evangelical theologians, pastors, and leaders put out what they called the Nashville Statement on sexual morality. According to Andrew Sullivan, it has “almost nothing to say to 97 percent of humanity on sexual matters. What it does instead is condemn the 3 percent.” Photo courtesy of New York Magazine

In my insecurity and my inability to relate to people around me, I judged the honest questions my fellow thespians were asking to be irreligious and antagonistic.

I didn’t understand at the time that the truth is often found beneath the surface of words. I didn’t understand how ruthless and damaging the institutions of religion could be to those who were questioning the existence of God. I didn’t understand that a powerful reaction to religion only came from people who actually cared about God.

I should have listened better.

The actors around me each had their own story about religious institutions, a difficult childhood experience with faith — and like a compass, those negative reactions revealed True North.

My new friends in theatre especially reacted to hypocrisy. They hated what they saw in churches, the many pastors who lacked empathy for people who questioned God, the condemnation of people who had been born different — LGBTQIA. They hated the way people in power, especially those in religious organizations, ignored the poor, the stranger, the refugee, the minorities. They hated the way women were abused, shut down, and silenced.

They saw with the clarity of vision given to all artists that Christian faith has been seduced and co-opted by political leaders.

Honest Reactions

Back in the late 1980s, I was confronting this conflict in the theatre for the first time.

Born different, my thespian friends wanted an authentic experience with God, and nowhere in the evangelical church could they find this. Frustrated, unable to leave their conflict behind, they turned away — some in disappointment, some in frustration, some in disgust.

A small group from Steven’s theatre class at Richmond College pays for their meal at a cafe during a trip to Greece in March 1989. The group was a particularly close ensemble led by theatre director Michael Barclay. Photo by Steven Denlinger.

It would be years before I realized that Christ reacted in the same way as my theatre friends. It would be years before I realized that faith laced with hypocrisy and fear towards all things different was not faith in Christ. It would be years before I realized that the reactions of my thespian friends revealed a passionate need for something larger than themselves.

They were disgusted, frustrated, and disappointed by people of the church who had blocked their path to God.

I couldn’t have known at that time that my fellows were actually searching for faith, but had been so devastated by individual experiences with abusive religious leaders that they couldn’t return.

Today, I know that many of my friends had been sexually abused — some by the religious leaders who claimed to be guided by God.

It was the negation of the negation, and because my friends were beautiful and talented and vulnerable, they were ripe pickings for such abuse.

They were all looking for another way — and for many of them, the only place that offered them full-on acceptance was the theatre.

Moment of Shame

The most shameful aspect of this for me is how blind I was to the real plight the theatre community faced, a plight still kept invisible by evangelical Christian leaders.

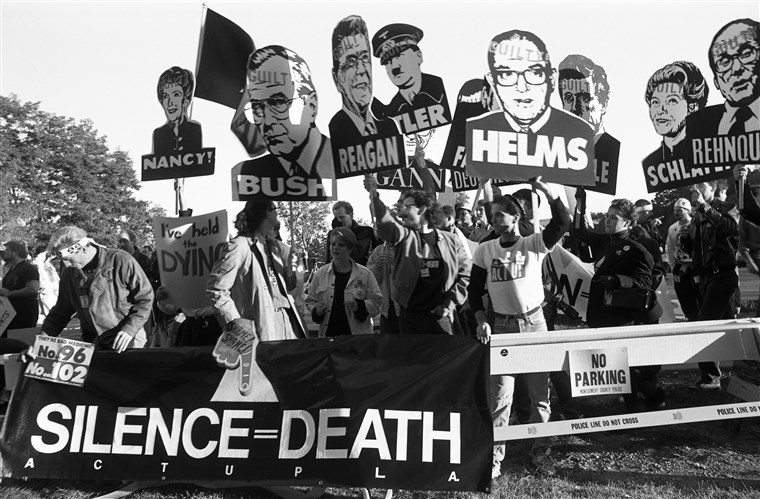

During the raging years of the AIDS epidemic, the church — represented by the arrogant efforts of the Moral Majority — remained indifferent to the problem. Or they spent their energy fighting any efforts to find a cure. Many evangelicals believed it was a scourge sent by God to wipe out the gay population.

Courtesy of NBC News

You have to wonder how they felt when they realized that straight people could also become infected.

You have to wonder how they felt when they realized that since the start of the epidemic in 1982, according to the World Health Organization, over 76.3 million have become infected.

You have to wonder how they felt when they found out that 39 million have died of AIDS since 1982.

To be continued …

Next week, I’ll look at how I found grace in the theatre in Part 2 of this blog.

If you like what you are reading, please follow our Soul Teachers website and “Like” us on Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn. Or you can reach me at StevenDenlinger@thesoulteachers.com. The first six episodes of our Soul Teachers podcast, which I host, are in post-production and will soon begin airing weekly.

Thank you Steven for sharing your ‘self’ from the heart. I look forward to Part 2.

Thanks, Art. I appreciate your support.

I appreciate your candour and insights! I came from the same conservative tradition (albeit the Mennonite versus the Amish background) and remember your smooth, lyrical voice in David the Shepherd Boy. One thing I have learned from Catholics is that God can be found in everything – even theatre! It is surprising where God shows up when our eyes are open and it’s not where many would expect.

Shalom!