I FIRST MET Walt Walker when I was a junior at Malone College in Canton, Ohio. I was studying to be a teacher, and the requirements for an Ohio Teaching Certificate demanded I do ten weeks of student teaching.

I FIRST MET Walt Walker when I was a junior at Malone College in Canton, Ohio. I was studying to be a teacher, and the requirements for an Ohio Teaching Certificate demanded I do ten weeks of student teaching.

When I checked in at the front office of Hoover High School, principal Mr. Ted Isue came out to greet me. He had the placid smile of a diplomat, and his soft “Hello” instantly put me at ease. He led me past two secretaries, into his small office, dominated by a stained wooden desk.

A tall, thin man, dressed in a white shirt and red tie, rose to his feet, shoving his hand forward to greet me. His face was curious but friendly.

“This is Mr. Walker,” Mr. Isue said.

The conversation took off like a rocket.

“I wanted to meet you before I took you on,” Mr. Walker said, his voice bright. Without warning, a storm cloud passed over his face, and he began firing questions.

“What’s the latest book you’ve read? Why do you want to teach English? What is your GPA like in college? Where did you attend high school? Do you know your grammar?”

It unnerved me — I had been told this was a formality since schools don’t require an interview to student teach. But I tried to answer the questions honestly.

“The Mists of Avalon” by Marion Zimmer Bradley.

“I love literature, and I love working with young people.

“3.9 in English, 3.56 overall.

“Hartville Christian School, a small parochial school not far from here.

“I’ve been teaching it to high school and junior high students as a parochial school instructor for the last four years.”

Out of the corner of my eye, I saw Mr. Isue scanning papers, making notations. I could see it wasn’t my resume. At one point, he excused himself briefly. It was pretty clear whose decision this was. Suddenly, like a cruise missile, one of his questions hit its mark.

“But do you know your grammar?” Mr. Walker’s eyes were locked on my face. It was obvious this was a deal-breaker.

I thought back to those first worrisome days of college when I had taken an English 090 course in grammar. To be sure I had mastered grammar, I had taken it against the advice of my adviser — just to be sure.

“I think so,” I said slowly. “I got a 98% on the Grammar Proficiency Test we’re all required to take before we do our student teaching.” I paused. Mr. Walker just stared at me, obviously unconvinced.

Annoyed, I pushed forward as Mr. Isue slipped back into the room and into his desk, looking from one to the other of us.

“They told me it’s the highest score anyone has gotten.”

Unexpectedly, Mr. Walker’s stern face dissolved into a sheepish smile. His shoulders slumped.

“Sorry to be so obsessive about this,” he said.

I’m sure Mr. Walker intended to reassure me, but it was then that my stress levels spiked.

If he sees how much I don’t know, he’s sure to fire me.

Shortly after Mr. Walker strode from the room, Mr. Isue turned to me, taking in my stark fear, and offered a smile of encouragement.

MY FIRST DAY working with Mr. Walker — I did a semester of pre-observation — started badly.

I arrived at Hoover High School early, dressed in formal slacks and a sweater, and promptly locked all my books in my little Ford Lynx. It was long before the days of cell phones, so I rushed into the building, making my way up to Mr. Walker’s room.

He greeted me with a brilliant smile — clearly, his reservations were behind him — and I tried to explain, the words coming out in a rapid jumble. Quickly understanding the issue, he put his hand out on my shoulder.

“Slow down, it’s okay. You just go down and figure out your car situation. When you’re done, you can come on back. It’s no problem at all.”

Like a father, he gave me a gentle pat on the shoulder.

“Go on, now. I’ll survive here in the classroom without you until then.”

His sarcastic humor was lost on me — but I got that he was understanding. Around us, girls and boys, dressed in preppy clothes that spoke of pride and style, streamed into his classroom. He turned and followed, leaving the door open. I heard his confident voice, rising above the crest of teenager’s voices.

“All right, open your composition books to page 215…”

I felt the hard knot in the pit of my stomach begin to dissolve as I turned and headed back down the long, empty hall to the main office.

SEVERAL MONTHS LATER, my first observation behind me, I found myself standing in front of my first class, a lively class of freshmen who looked at me with curiosity.

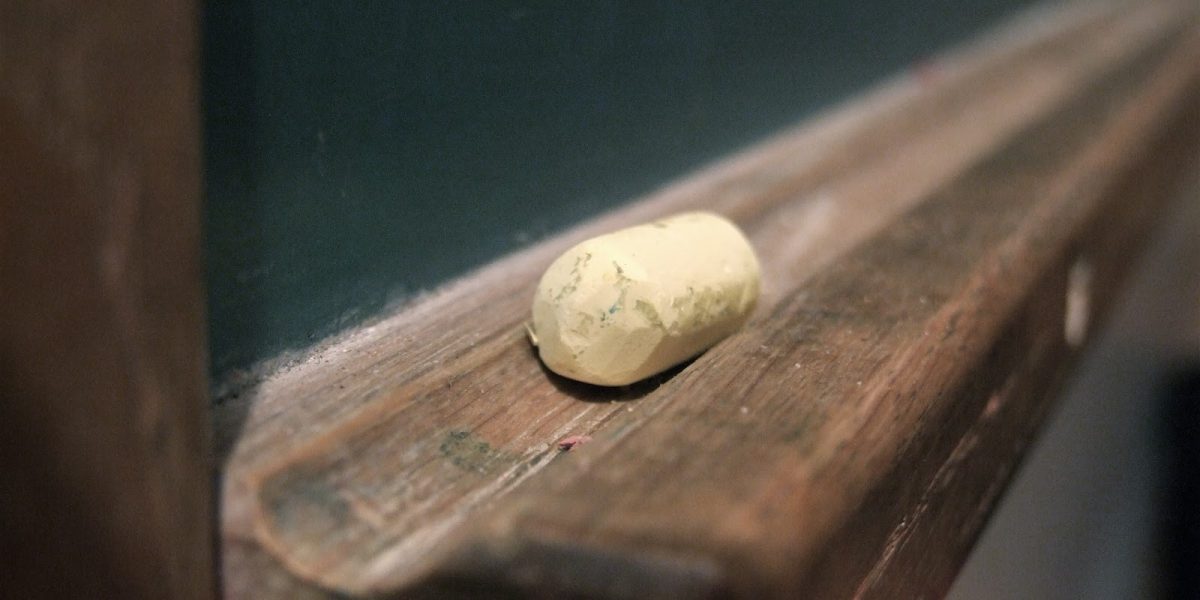

The neat rows of wooden desks were filled to capacity. In the back, Mr. Walker took notes on a pad. Near the front, across the aisle from each other, two girls giggled and showed each other their notes. Toward the back, a boy with flaming red hair slouched back in his seat, skepticism lurking on his face.

After the first class, during Mr. Walker’s planning period, he sat me down in the classroom.

“I have a few suggestions,” he said. “The next time a student asks you a question, don’t give him the answer. Turn his question into a question for the entire class.”

During the next class, a girl sitting in front raised her hand.

“In the Prologue, does Shakespeare intend to prove that love is fated, or do we have free will?”

It was a good question, better than I expected from a freshman. I was tempted to answer it. But instead, I turned to the class.

“What do the rest of you think?”

Instantly, a field of waving hands. This class had obviously done its homework.

I pointed to a student. In the back of the room, Mr. Walker smiled and jotted down a note.

UNEXPECTEDLY, IN THE fourth week of my student teaching, I arrived one morning to find a substitute standing at the desk in Mr. Walker’s classroom. He looked at me searchingly.

“I’m supposed to just watch you teach,” Mr. Substitute said, a little bitterly. I looked around.

“Where’s Mr. Walker?”

“Oh, he’s home, sick. You’re supposed to call him at the end of the day. He left you his personal phone number here.”

The day went quickly, with the occasional student asking about Mr. Walker, but by now I had all of his classes firmly in hand, and the day went smoothly. At the end of the day, I called Mr. Walker.

“It’s my back,” he said, his voice clear and nasal over the wire. “Could be awhile.”

IT WAS A WHILE. In fact, it was four weeks. By the time Mr. Walker returned, I was finishing up my last week. As Mr. Walker observed me teach his classes that day, he was all smiles.

At the end of the week, after I finished my last class, he appeared at the door. “Here’s your recommendation letter,” he said, handing me a copy.

I held it away from me, worriedly.

“Go on, you can read it,” he said. “I always give my recommendation letters to my students. It helps them see how they’ve really done.”

I scanned the letter. His kind words contrasted starkly with my first impression of him. Mr. Walker settled into one of the desks. When I looked up, he was smiling proudly at me.

“The student teacher I had just before you … was such a disaster,” he mused. “She dressed like a model, but she didn’t know anything about grammar.” He chuckled, then grew serious. “I was spending two hours a day after classes, just teaching her the basics of sentence structure.”

“So that’s why … in our interview …”

“Yes. That’s why. I had sworn I would never take on another student teacher, but your letter and that interview convinced me you’d do well.

He rose. “And you have.” He gestured to the letter. “It’s all in there.”

I SUPPOSE IT could have stopped there. But it didn’t. Several weeks later, I got a letter at home with a Louisville postmark and return address: Walt & Doris Walker.

I tore it open. By then, I was finished with my semester, the grades having arrived in the mail.

Inside was a note scrawled in Mr. Walker’s distinctive handwriting, along with a personal check.

The note was simple. “The stipend I received for being your cooperating teacher — my wife and I talked it over, and I’m giving it to you. I was out for most of your student teaching. You really did the work. You deserve this.”

The check was written out for $100. I knew money meant something to my new mentor. The fact that he would give me the stipend — it said something about how he felt.

His gift also meant a great deal to me. I was saving for my year abroad, working heavy construction sometimes 12 hours a day. I had no time to acknowledge the gift. It was a brutal summer.

Several nights later when I returned home, my mother told me Mr. Walker had called her.

“He wanted to make sure he hadn’t offended you. He hasn’t heard from you. And he’d like to have you over for dinner.”

I remembered how much I had learned from him as a teacher in the classroom. I remembered sitting across from him and his wife at a Friendly Restaurant in North Canton eating a Reese’s Pieces Sundae after attending the Hoover’s spring musical. I remembered the way we laughed together about moments in the classroom.

And I finally picked up the phone.

I NAILED DOWN a teaching position within a month of returning from my year abroad in May 1989. I had kept in touch with Mr. Walker across that year — by now, he had encouraged me to begin calling him by his first name, Walt — and I knew I wanted to spend my teaching career at Hoover High School, but the English department didn’t have an opening that first year.

Shortly after I began my student teaching, Walt had begun strategizing with me, laying the groundwork so that I would have the strongest possible chance of getting a teaching position at Hoover after I graduated from college.

For example, toward the end of my student teaching, he suggested I ask Mr. Isue to observe me teach. When I graduated from college, Walt suggested I let him know I wanted to work at Hoover, but that I’d be taking a position somewhere else until a position became available.

“This will ensure that Mr. Isue doesn’t forget you,” Walt said.

Walt also made it clear that he believed Hoover was the place I belonged — and that he intended to do everything in his power to ensure that I was hired.

So during my first year of licensed teaching at Central Christian School in Kidron, Ohio, as I slogged through my middle school English classes, I rested in the understanding that I was a guaranteed shoo-in for a high school English position at Hoover.

It was my destiny.

And sure enough, by April, one of Hoover’s English teachers had announced her retirement. By then, I knew I didn’t like teaching middle school students. I couldn’t wait to begin my real job as a teacher of high school students.

Walt was very positive about my chances. In fact, years afterward, one of Hoover’s teachers told me that the schedule Hoover offered its incoming candidate had been created with my strengths in mind: British literature, World Drama, Shakespeare, and Freshman English. It was the perfect position for the right teacher.

Except, as it turned out, I wasn’t the right teacher.

EVEN TODAY, I cringe when I think about the mistakes I made that spring, the assumptions I carried as I completed my first year of teaching middle school at Central.

The previous June, I had been joyfully welcomed with high recommendations from my mentor, and from other teachers in the school who knew of me. I got an interview by word of mouth: I stopped at Central Christian with an influential friend to visit. He introduced me in hyperbolic terms, and voila, I found myself in a job interview (I filled out the job application afterward). It was clear they wanted me. Several days later, I was offered a teaching contract.

But the man they employed was not the man they hired.

I had just spent a year abroad and was questioning where I fit into the world of evangelical Christianity. With all of my angst, I was not equipped to teach middle school students, an adolescent level known for insecurity and doubts — they were singularly uninterested in a teacher who overshared about his dark night of the soul.

I didn’t understand professional boundaries.

When things went south for me — student reactions to my inexperience, my arrogant approach to students, and a clear disinterest in the job for which I had been contracted — my principal bent over backward, offering me a professional growth plan.

But I refused. I offered to resign, which my principal promptly accepted.

That’s when I called Walt. When I explained on the phone what had happened, his voice exploded across the line, scorching my ears.

“Steven, all you needed to do this year was complete your first year successfully. This is bad.” Silence. And then, “This is bad. I’m not sure what I can do.”

My mouth went instantly dry. I had never seen him angry at me.

When I hung up the phone, I left my bedroom in the apartment I shared with a college friend and walked into the living room, looking out towards Interstate 77 South.

My stomach had turned to acid. I didn’t feel like crying, although I wished I could. I wanted to fix this, and I couldn’t.

It was then I really understood how far out to sea I was, how deep the water beneath me plunged.

EVENTUALLY, I PICKED myself up and secured another teaching position. Four years later, I returned to Hoover as a full-time English teacher, having earned my stripes with four years of successful teaching and a network of professional relationships. By then, Walt and Doris had become my second set of parents.

As I settled into my role at Hoover, minutes from their home, my time spent with Walt became even more frequent. Now a journeyman teacher, I often stopped by for dinner, talking long into the evening about teaching and politics.

Reared on homemade, Amish-Mennonite meals, I learned there were other ways of cooking. I mastered the art of grilling a delicious steak. I learned there was a cook named Julia Child. I watched Walt meticulously create complex dishes with spices I could barely pronounce.

I also learned that conservative Mennonites and conservative Republicans were not the same brands of humanity. Walt was unabashedly a Republican who was also socially liberal.

He understood money, and the economy, and probably due to his influence, I ultimately became a Blue Dog Democrat. My M.A. in English (and theatre) at The Bread Loaf School of English at Middlebury College and Oxford gave me a social conscience to complement the fiscal conservatism I gained from Walt.

Most importantly, Walt taught me how to disagree with civility in the political arena.

I remember writing a newsletter while in Europe — about 175 people received it once a month. I described with great sympathy a party I had been to in which Palestinians had celebrated their Declaration of Independence. My words were pompous: I was fairly uninformed of their “struggle.”

Walt’s words in his next letter were informed but civil.

“I’m glad you’re getting to interact with people from other countries. But not everyone here in America thinks the Palestinian Declaration of Independence is such a good idea. We remember the suicide bombings.”

There was no condemnation in his words — he was respectful and kind, with no arrogance — yet the message got through. I remembered the good-natured perspective he brought to political discussions with his colleagues (he was one of the few conservatives on a faculty that skewed liberal), the way he was able to bring laughter to the table during moments that could have been tense.

His words and example taught me to approach politics differently. In the many conversations we had over the years, he always listened to my positions carefully, respected me when I disagreed with him, and ultimately, let me go my own way.

Sometimes, he even followed. In fact, in 2008 when the Crash occurred, he rejected the Republican party and voted for the Democratic candidate for the first time in his life. He returned to the GOP two years later, but his voting choice proved him to be a socially conscious Republican, not a blind partisan.

SEVERAL DAYS AGO, I called Walt on the phone to check in. We didn’t have much time — it was clear he had visitors and he said he needed to go.

But Trump had just announced a wave of upcoming tariffs, and there was a potential meeting with Kim Jong Un. #MeToo was dominating talk of Hollywood. But Walt’s health was good, he told me.

“I have to go” — Walt’s voice was clear and his mind alert — but we should probably talk soon about what happened at the Academy Awards, what is happening politically.”

I agreed and hung up.

MY MIND RETURNED to that moment right after I had secured a new job and found my way back into teaching high school students again.

It is probably that moment that made him the great Soul Teacher he is for me today.

I remembered calling Walt to thank him for his help. I remembered the relief I heard in his voice, the sheer joy he clearly felt in seeing me resolve a very difficult situation. I remembered him calling me back to invite me to dinner in downtown Canton. He told me to dress up. Bender’s Tavern was a formal restaurant.

When I arrived at the entrance to the restaurant, he met me, looking approvingly at my well-heeled appearance.

“Congratulations again on your new position,” he told me. “It’s good to be employed.”

Over dinner, he gave me some perspective.

“My wife and I have decided to treat you like one of our children,” he said. “At times, our children do very foolish things, but we still love and support them.”

He also shared a bit of advice.

“The next time you need to move schools, wait to resign until you have a contract in hand from your next school.”

It was a tough lesson, and one I didn’t forget.

Well written and inspiring!

-Jennifer Isue Todd