I WAS SEVERAL years out of my Conservative Mennonite community before I ran into the author Philip Yancey. During that confusing season, I somehow managed to join, piecemeal, an Episcopalian church, a Presbyterian church, and a nondenominational church.

I resented the exclusive nature of my childhood church, their firm belief that nowhere on the planet was God’s will more complete than within the simple garb and restrictive culture of my childhood community.

Fundamentalist, evangelical Christianity.

Then came the final seduction — the warm embrace of Rome. I need people — it’s who I am. Disconnected from my entire network of friends, living two hours south of my conservative Mennonite community, completely on my own for the first time, loneliness begin to bite. All around me — while teaching at Steubenville Catholic High School — I saw warm-hearted families who loved each other passionately, and I wanted in. I craved the security that comes from being part of a tight-knit community. With Catholicism, I got all that, only without the weird dress code.

Never mind that the Roman Catholic Church taught they were the sole stewards of God’s grace. Never mind that my Anabaptist tribe remembered every single martyrdom committed by Holy Mother Church during the persecuting bloodbath we now call the Reformation. Never mind that my father daily prayed that his son would return to the lifelong vows he had made on bended knee at the tender age of 12.

All of that was flung aside once I experienced the exotic chants, the wondrous beauty of high church liturgy, patriarchal families and their beautiful Eastern European daughters. This world tapped the deepest recesses of my soul. I became convinced that my family was wrong, convinced that I should consummate my faith within the True Church, convinced that God had placed his finger upon my soul and called me to serve him more completely within the ancient traditions of Roman Catholic faith.

Convinced, that is, until after a glorious Easter Sunday in 1993 when I entered the church and experienced my first Mass. It dawned on me – having seen converts enter the conservative Mennonite world and finding themselves never quite accepted as those who have grown up with in our world – that truly being part of Catholicism was never going to happen to me in this lifetime. Suddenly, my certainty left me, and I abandoned the comforting arms of Holy Mother Church. I was done with Catholicism. Once more, I was at loss. This time, I didn’t return to any church — Catholic, Protestant, or Anabaptist — for another three years.

But after a wonderful summer of graduate school at Oxford University, I wandered into a Sunday morning service at a different (more liberal) Mennonite Church, listened to a savvy analysis of culture by a thoughtful pastor who was also working on his PhD, and once again, my deepest spiritual passions were set aflame.

I returned the next Sunday. And the next.

Perhaps it was the understanding pastor who often met me for breakfast, perhaps it had something to do with the charming girlfriend there who quickly found me, perhaps I really was living within an enchanting Hallmark Christmas film (with lazy snowflakes, and a Christmas tree that needed decorating) —

Okay, don’t ask.

As I said, it was a confusing season in my life.

MY CLOSE FRIEND John Fohner watched all this religious flailing about with a blended air of sympathy and amusement. Finally, he decided I needed some advice.

“You should read Philip Yancey,” he remarked during one of our late-night chats. We were sitting at the kitchen table of his home, his wife wiping clean the white electric stove where he had earlier made a large pot of iced tea.

“Yancey reminds me of you,” John said, draining the last of his iced tea. “He’s a bit of a wanderer, at least when it comes to his faith.”

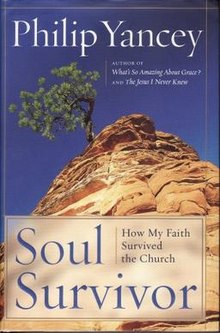

Several weeks later, I picked up a copy of Yancey’s Soul Survivor at a local Christian bookstore. I scanned the Table of Contents. It encompassed the biographies of 13 people who had influenced him: artists he admired, authors he had read, political figures who changed the world — all who had made a significant impact on his thinking. I recognized some of my own heroes: Martin Luther King, Jr., G.K. Chesterton, Leo Tolstoy, Dr. C. Everett Koop.

But it was Yancey’s prologue that intrigued me. His story sounded a great deal like mine.

Yancey reveals a childhood in which he was nurtured to an enduring faith by men and women who were blatantly racist. He shows moments in which blacks were rejected by his childhood faith communities. He analyzes the private school movement in the South and admits the primary reason for their creation: to exclude black children from the beloved white sons and daughters of evangelical families.

His world felt intimate and familiar.

One church I attended during formative years in Georgia of the 1960s presented a hermetically sealed view of the world. A sign out front proudly proclaimed our identity with words radiating from a many-pointed star: “New Testament, Blood-bought, Born-again, Premillennial, Dispensational, fundamental…” Our little group of two hundred people had a corner on the truth, God’s truth, and everyone who disagreed with us was surely teetering on the edge of hell.

His book was a revelation. “He recognizes the problems, yet he still stays within that evangelical community?” I thought. “How does he do that?”

I had grown up with that sanctimonious attitude, as well. I knew what it was like to listen to preachers who spoke with assured authority, telling us that although most of the world disagreed with us, we were still right.

“Narrow is the path,” we were told. We could rejoice we were on it.

It didn’t seem to matter when that “narrow path”chose the wrong turn, or when its promulgators were actually proved wrong.

So yes, I identified immediately with Yancey when I read his prologue.

Because Yancey was onto something more significant than racism.

Later, I came to realize that the church had mixed in lies with truth. For example, the pastor preached blatant racism from the pulpit. Dark races are cursed by God, he said, citing an obscure passage in Genesis. … Armed with such doctrines, I reported for my very first job, a summer internship at the prestigious Communicable Disease Center near Atlanta, and met my supervisor, Dr. James Cherry, a Ph.D. in biochemistry and a black man. Something did not add up.

Growing up in Northeastern Ohio, I had never heard any sermons that were blatantly racist. But I could identify with another issue Yancy tapped. The title of his book Soul Survivor — one he has publicly stated is his favorite — gives you the most powerful clue.

Yancey was cutting to the heart of an existential issue found within literalistic, fundamentalistic churches.

It’s where I connected with Yancey— just as my friend John knew I would.

WHAT DREW ME into Yancey’s biographical stories was his core question — What does it take to leave an insular Christian culture without also abandoning one’s faith?

When I left my conservative Mennonite community at the age of 25, I believed at my core that faith was worthless unless it made sense to the outside world.

Yet my childhood faith taught me to flee secular culture, even aspects that showed God‘s creative power most clearly.

Theater. Dance. Fashion.

According to my childhood community, these were the real dangers.

It took me years to see that the real sins were far more complicated — all of them connected to my idiotic pride.

I was afraid to take chances. I was afraid to become vulnerable. I was afraid to learn.

I had left my Christian enclave, desperately afraid I would lose my faith. Yet only outside was I able to find it.

Inside, I had feared my father might be right — that leaving our culture with all its strictures meant eternal damnation.

So as I began to read Soul Survivor, I was desperate to know how Yancey had escaped.

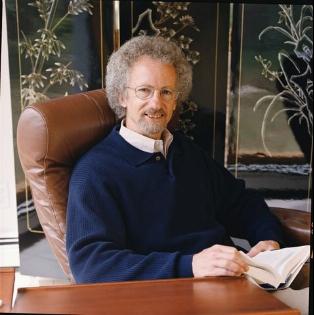

I SEE THE answer now even in Yancey’s photo, found on his webpage. His hair is uncontrolled. Curls surround a hopeful face that peers out into the world, curiosity written into every wrinkle.

His journey might have been my own journey:

“I went through a period of reacting against everything I was taught and even discarding my faith. I began my journey back mainly by encountering a world very different than I had been taught, an expansive world of beauty and goodness. Along the way I realized that God had been misrepresented to me. Cautiously, warily, I returned, circling around the faith to see if it might be true.”

Moments like these caused me to devour his book, parsing his stories and insights.

EVENTUALLY, I CAME to realize why I had left my insular culture. I began to identify with Yancey’s reactions to his own religious community. I embraced the principles Yancey promoted.

But this didn’t occur until I discovered — at the age of 46 — a second book written by Philip Yancey: What’s So Amazing About Grace?

There, he takes bold perspectives on some of the toughest issues Christians face. And the operating principles he laid down still apply today. In fact, the greatness of Grace lies in Yancey’s ability to transcend the political era during which he wrote the book.

Please understand, Yancey does not encourage Christian leaders to meekly submit to the prevailing tides. On the contrary, his call to action demands courage and discipline — and are unlike those offered by most Evangelical Christian leaders today.

In fact, I would argue that it took Yancey’s understanding of the role of faith in the public square — as outlined in Grace — that made it possible for me to identify as a Christian today.

I’ll explain why next week in “Philip Yancey: Resisting Grace (Part 2).”

I concur that what was missing for us was grace and I love Yancey’s perspective. I find myself standing on tiptoe, straining to see through that window.

That’s a beautiful image, Cindy.

Though I have heard of Phillip Yancey for years, I have yet to read anything he wrote. I have, however, read The Chosen and My Name is Asher Lev, both my the late Chaim Potok. In those novels he, as an Orthodox Jew with a PhD in Philosophy, addresses what it is like to live within and outside of a particular culture, existential issues of keen interest to me as a “cradle/ethnic” Anabaptist-Mennonite.