Although severe, my principal modeled attention to detail — a skill I needed to survive a career

To read “Kenneth Voss: The Letter (part 1),” please click here.

MR. VOSS WAS an object of speculation and fascination to the students and teachers. I saw him arrive once, zipping across the parking lot in a white, sporty car — with David Bowie music blasting from the speakers.

Yet as principal of Catholic Central High School, he was an eminent grise, a figure who brought fear to my heart.

I learned to dread his notes in my box. They were formal, unyielding, straightforward.

“Mr. Denlinger, as I visited your classroom yesterday, I noticed some students don’t have their books covered. Please ensure they are covered properly.

“Mr. Denlinger, two of your students during assembly today were giggling. Please ensure that they focus. You are here to teach them how to learn.”

“Mr. Denlinger, your lesson plans do not include grammar. This is an important part of our state-approved curriculum. Beginning immediately, I expect to see you teaching and evaluating your students in this area.”

I was not the only teacher who received notes like this. Mr. Voss had arrived at the school several years before me, and he seemed to have few fans. The school board had given him a tough mission.

Today, I understood his challenge.

Back then, not so much.

The school enjoyed a century of pride and tradition, but according to the gossip feed, Catholic Central had been on the verge of bankruptcy. Due to his financial acumen, Mr. Voss had been hired to save it. The tight-knit community who sent their kids to this school believed any sacrifice was worth making.

CCHS was on the verge of bankruptcy. Due to his financial acumen, Mr. Voss had been hired to save it. Doing this meant stepping on toes.

Doing this meant stepping on toes, and the veteran teachers resented the changes he made. We had to limit our use of the copy machine, for instance. We couldn’t spend school monies for extraneous clubs like the drama club or the student newspaper.

Mr. Voss was a born micromanager. He rescued the school by paying attention to the details. His crisp notes, his scrutiny of minutia — nothing escaped his unsparing eye.

Perhaps it’s why attention to detail has become part of my definition of professionalism.

THERE WERE HARD lessons to be learned as well from Mr. Voss. I was a young teacher, and probably more naive than most.

One situation I’ll never forget: a junior had failed my English class. Let’s call him Adam. I don’t remember the reason he failed, but most likely, he didn’t turn in his work. Shortly after grades came out, I took a phone call at my parents’ home in Hartville.

As I did every summer, I was doing construction work. It had been a long day, but I got up from dinner after my mother answered the phone and gestured to me.

I recognized the voice immediately — that of a highly successful lawyer who claimed he was a “friend of the football team.” I had taught one of his children over the past year. In gratitude for my good work, I assumed, he often invited me to join his family for lunch on Sundays after mass.

At the local country club, of course.

Mr. Lawyer always paid. For a penniless teacher, this meant something. Unfortunately, at that point, I didn’t understand what the term conflict of interest meant.

I was about to be schooled.

“Mr. Denlinger, I’m calling to ask your help.” The abruptness of his tone told me that this wasn’t a friendly call.

“Sure.”

“One of our running backs has failed your English class. You remember Adam? He’s a good boy.”

“Oh, yes. Adam.” I mentally flipped through the gradebook. “That’s right.”

“So it’s true.” There was a brief pause. “Mr. Denlinger, you’re a reasonable man. Isn’t there something you could still do to pass him? With a failing grade, Adam won’t be able to play football this fall. Our team could lose our shot at State.”

I hesitated. His voice became warmer.

“Steven. I know Adam tried. He even turned in his research paper.”

I knew what Mr. Lawyer wanted. There wasn’t much subtlety here. But at the age of 27, I had never faced such a crisis. Here was a powerful community member, blatantly asking me to change a grade. Worse, he was accusing me of keeping the team from going to State.

Today, as I think about this moment, I wish I could go back and give my younger self some wise advice.

“Steven, you need to make it clear you won’t change the grade. Then you need to hang up and call Mr. Voss. You repeat the phone call to him, word for word, so he can support you. He does not want to be surprised when this powerful lawyer calls him. Because that will be his next step.

“And most important, you need to be very careful with your words, because this lawyer will throw you under whatever bus comes by in order to make sure Adam can play football.”

You see, according to Catholics in Steubenville, on the Seventh Day, God didn’t create the Sabbath: he created high school football. In fact, when a boy child was born at the local hospital, the booster club showed up to welcome the birth of the infant, and stuff a brand-new pigskin in his cradle.

In Steubenville — after taking in the sweet essence of his mother — the first scent a boy inhales is fresh leather. There’s a reason Steubenville schools win football games.

And there was no greater rivalry than that between Catholic Central and the local public school, Steubenville Big Red. The winners of the City Championship ruled the county.

My lawyer friend wanted to make sure that next year’s City Champion was Catholic Central. He was not about to let a first-year teacher — someone he believed could be easily influenced — block that dream.

Unfortunately, I wasn’t there to advise my bad self.

I waited a moment, uncertain of what to say. I wasn’t about to change the grade. So reluctantly, I passed the buck.

“You know, even if I wanted to, I still couldn’t change the score. Mr. Voss would never allow it.”

There was another moment of silence as Mr. Lawyer paused to take in my comment. Then his voice turned cheerful.

“Well, thanks for trying to help.”

It wasn’t more than an hour before I got another phone call, this one from Adam’s mother. She didn’t even try to be subtle. She flat-out asked me to pass her son.

Feeling bad for her, I tried to express my sympathy.

“I wish I had known Adam’s failing grade was going to keep him from playing football. Perhaps we could have done something about it.”

Today, as I look at that line, I understand why those two conversations blew up in my face. Innocently, I believed that we were having a private conversation. I could not have known how public that conversation would become, how far these words would travel.

MY PRINCIPAL REACHED me an hour later. This time, I took the phone call in my bedroom.

Mr. Voss’s voice was cold.

“Mr. Denlinger, I just received a surprising phone call from Adam’s mother. You told her you wish you had known Adam’s failing grade would keep him from playing football? Is this true?”

I froze, fear blanketing my mind, stopping me from thinking clearly. He took my silence for assent.

“And then I receive a phone call from a very prominent lawyer, who told me you said you couldn’t change the score because I wouldn’t let you?”

My mouth had gone dry. I struggled to speak.

“That’s not what I meant.”

“Really?” The voice had gone icy. “What did you mean?”

“Uhm, I —”

“Actually, I’m not really interested in what you meant,” Mr. Voss said. “I’m concerned with what you said. Because this has become a big problem for me. If you have so little integrity that you’re willing to change a grade because the football team might otherwise lose, perhaps you’re at the wrong school.”

And then the phone was buzzing in my ear.

I stood there, staring at it.

I was about to lose my job again. Only this time, I’d have to admit I’d been fired. For lack of integrity.

I sank onto the nearby bed. I wished I could cry. I didn’t know what to do.

WHAT GOT TO me was his accusation that I lacked ethics. I knew otherwise.

The next day was endless. As I mixed mud and carried block for my construction boss, my mind ran in circles. I wondered if I’d lose my job.

I sank onto the nearby bed. I wished I could cry. I didn’t know what to do.

Finally, I decided I needed to write a letter, defending myself.

By the time it was done, it was over two-and-a-half pages, single-spaced.

Dear Mr. Voss:

I am writing this letter to clarify several things about our phone conversation on Friday evening, June 28, 1991.

Yesterday evening when you called me, I was thoroughly unprepared for the conversation we had. Since I do not always think fast on my feet, I was unable to clarify exactly what I had said in my conversations about Adam’s grade. Thus, the answers I gave were unclear and seemed to hedge. Under your probing — I am afraid — my mind went blank and my answers were poorly, defensively, and inaccurately given. Therefore, upon reflection, I am writing this letter to explain the situation.

When I think about my feelings during that time, the panic that dried out my mouth made it impossible to think straight.

Today, as an experienced teacher, looking over my detailed explanation of what happened, complete with lines I bolded to indicate which words I would emphasize if I were speaking it to him, my desperation to keep my job come through clearly.

At that point, my entire identity was tied up in my role as a teacher.

First and foremost, I do remember telling Adam’s mother that if I had known Adam’s failing grade would keep him from playing football, perhaps we could have done something about it. I should have emphasized Adam’s responsibility. She misread this comment. I meant that perhaps we could have assigned tutors, provided extra help, done something to help him help himself. However, it angers me to the point of emotion when I consider the way the family has twisted my comment.

What comes through clearly in the letter, though, is what I felt was the attack on my integrity. I had taught in parochial schools before and during my college years where moral integrity was a teacher’s primary certification.

This accusation touched my most horrifying nightmare.

In my six plus years of teaching, I have held to the strict ethic that I decide the grade of a student based upon performance and effort, not on what the consequences of the grade will be. I have taken heat in the past for controversial grades and will do so again if need be.

The other thing that I notice — now 28 years removed from that experience — is the earnestness, and the assumption I wore like an ubiquitous pair of glasses that others believed I am a truthful, good person.

Throughout the year, I have consistently made a point of holding up honesty and justice to my students as essential to integrity. Your charges on Friday evening stunned me. Hence, my answers were uncertain and unclear. Those charges struck at the root of my integrity. Instead of denying the charges right away, I hesitated to answer you — I wanted to be certain that my response was honest.

I should have denied the statement immediately — it was totally out of character for me and I didn’t remember saying it. However, at the time I did not remember what had been said in the conversation and I did not want to answer untruthfully. Therefore, my uncertain responses made me appear to be hedging.

It wasn’t until I began preparing to write this piece that I realized something new. I have always wondered what Mr. Voss thought of this letter — I’ve never actually asked him — but when I consider what he told me later, something clicked into place.

Mr. Voss needed my letter for legal reasons.

THAT FALL I returned to Catholic Central. Mr. Voss welcomed me, as usual, and the school year began. But about halfway through the year, during a teacher evaluation, he brought up the topic.

“You remember Adam?”

I nodded.

“Well, that case went all the way to the attorney general’s office in Columbus,” he said, grimly. “The parents insisted that you said you’d change the grade — if I had only let you.”

It was the first I’d heard of that battle since I’d played no role in it. It was a complete surprise — and yet, looking back, why should he have told me any earlier? I was just a rookie. Maybe he thought I would have just screwed it up more. Maybe he thought he was doing me a favor, not putting that kind of pressure on me. Whatever the reason, it was the first I’d heard of it.

“The parents insisted that you said you’d change the grade — if I had only let you.”

He considered me.

“We won. The kid isn’t playing. But it’s the sort of thing I don’t expect from a teacher like you. Don’t let it happen again.”

I wasn’t about to.

As I reflect back on that experience, it only now occurs to me that very possibly the letter I sent Mr. Voss gave him the documentation he needed in order to support his claim that I never intended to change the grade.

It was another layer of the lesson I needed to learn: professionals need to document what they say, because when you write down what you say, it becomes evidence one can use in court.

THE TIME I spent at Catholic Central looms large in my mind and memory, yet I was only there for two years, from the fall of 1990 to the spring of 1992. And the primary reason I left was because I was hired to direct a major drama program at a nearby public high school.

It also helped that they offered a salary increase of $10,000 — approximately a 33% increase in pay.

Perhaps I have such clear memories of Voss because he was exactly the right mentor I needed at that point in my teaching career. He was the Soul Teacher I needed to discover my core as a teacher. He helped me understand the meaning of ethical behavior. He helped me see what it means to be a professional.

I remember one afternoon in particular at my new school as I prepared my classroom for the first week of school. I was standing at the chalkboard, writing out my objectives for the week, when my new principal dropped by.

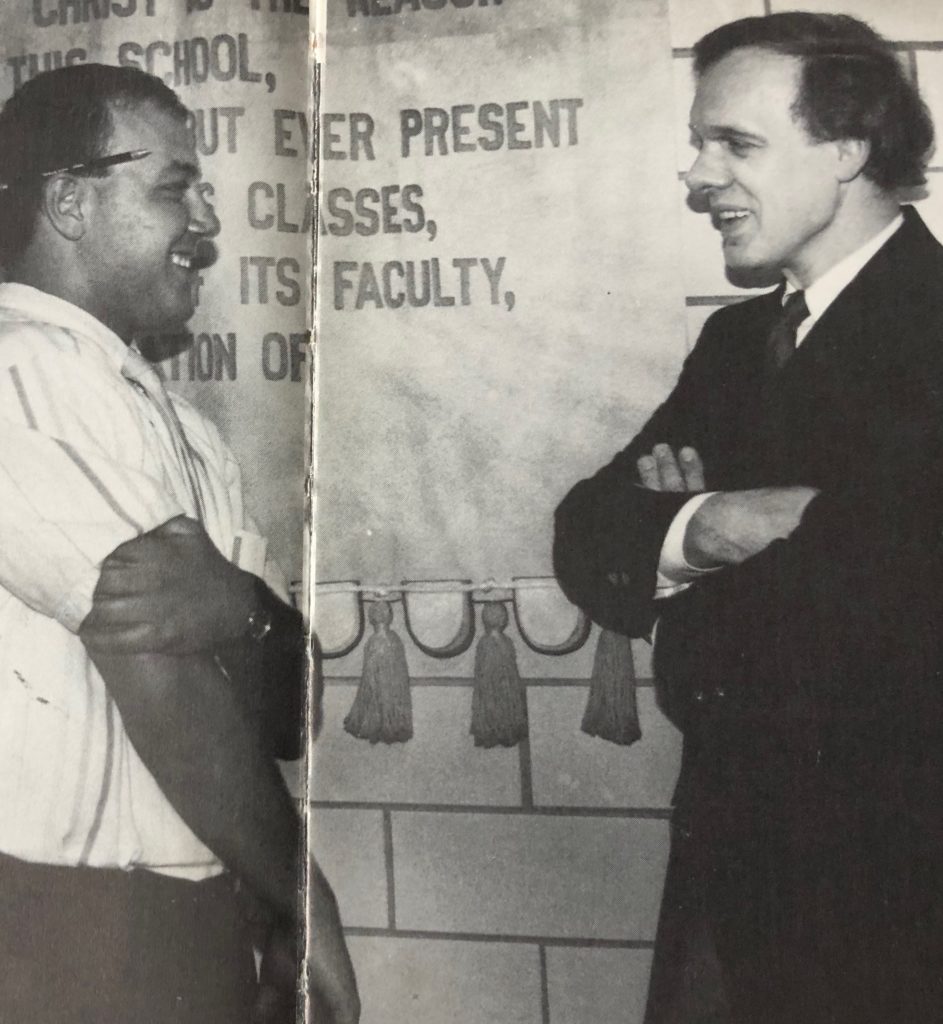

Everyone called him Rich. He was friendly and jovial, someone who loved to laugh with his faculty, an abrupt change from the thin and somber eminence who was Mr. Voss.

A pleased smile lit Rich’s face as he walked into my room, looking about. I stopped what I was doing.

“You know I spoke to your former principal at length,” he said. “We had a very good conversation about you.”

A feeling of dread crept down into my stomach. This could not be good.

Rich must have seen my hesitation.

“I was impressed,” he shot at me, stuffing his hands in his front pockets. “He gave you quite a recommendation. Clearly, he was sorry to lose you.”

He eyed me with a satisfied grin.

“Welcome to Big Red,” he said.

Wow! I remember all this too well of Mr. Voss. I just threw away all my notes from him of what I did not do.

You expressed your experience well and grew into an amazing teacher/author! Learned lessons are never forgotten!!

I was a student of Mr Voss at South Hills Catholic High in Pittsburgh, class of 71. Mr Voss could have made a outstanding overseer of a southern plantation. As an instructor, entrusted with the development of the minds of young men, he was severely lacking. How Mr Voss became a principle completely escapes me. I pray for the multitude of students and co-workers that were impacted by such a negative presence. And for Mr Voss himself.

Rodger Grady

South Hills Catholic H.S.

Class of 1971

He was a micro manager. I worked for him for one year and did not care for his school management style. When I became a school leader, I tried not to behave in the same manner. I wish him nothing but the best!!!

I was a student teacher for a few weeks at Catholic Central in the early 1990s. I found this story by chance when I Googled Mr. Voss after coming across a letter of recommendation he wrote for me. That was about 30 years ago! I kept the letter because it was so surprising to me. Mr. Voss said some very nice things about me and my work at the school. This surprised me. I was surprised because about the only thing I remember about Mr.Voss was him telling me on my first day at the school that he did not want student teachers in the school but he owed someone a favour. He was gruff. The football rivalry in Steubenville was fantastic.