An uncompromising principal, Ken Voss was flinty, obsessive, and nobody’s friend. But his leadership changed lives.

WHENEVER I MENTOR young leaders, I often reflect on the two years I spent in the sun-drenched Ohio Valley teaching in an ancient brick building where students wore neckties and plaid uniforms, and God attended football games dressed in blue and gold.

Catholic Central High School.

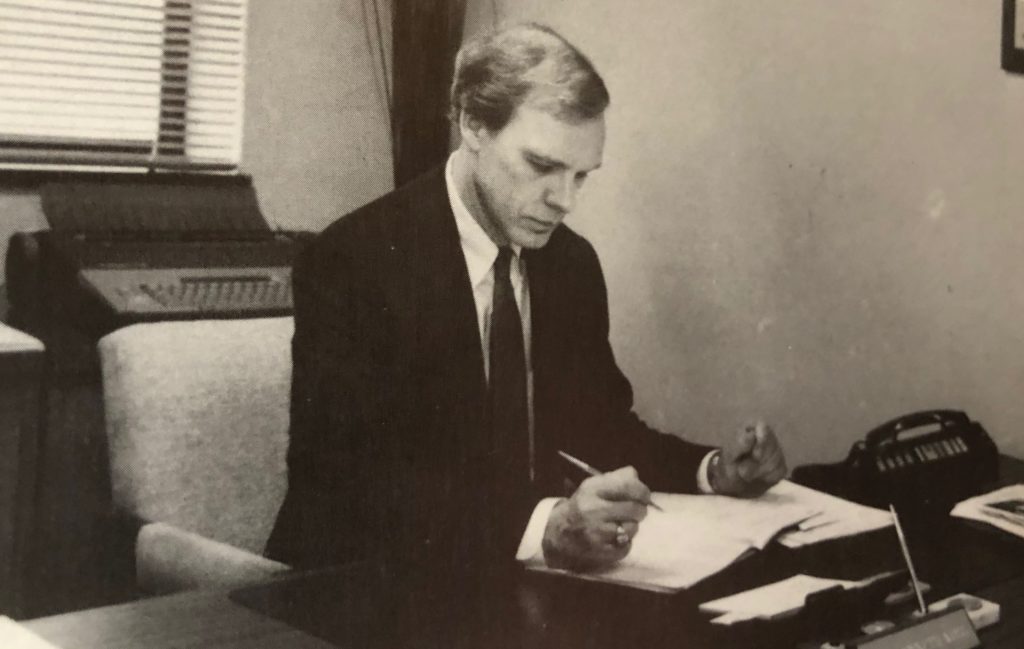

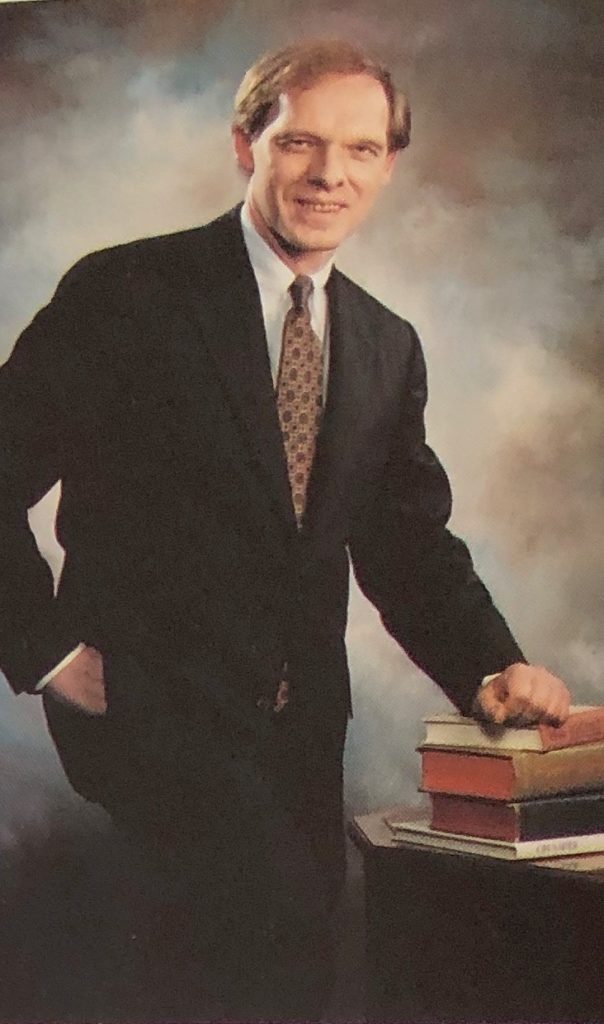

It was led by Mr. Ken Voss, an uncompromising principal who was flinty, obsessive, and nobody’s friend. But his leadership changed the lives of his faculty, his students, and the fervent community of faith who supported him.

At least he transformed mine.

Voss was someone who believed in the Old School (™) system of pedagogy. He believed classrooms should be quiet orderly places where students sat still, listened, and learned. He believed teachers should pay attention to the details of evaluation. He believed teachers should award grades based on what students achieved.

Today, I look back on those two years of my teaching career as a sort of boot camp. Under his severe guidance, I laid the foundations of my classroom pedagogy. In fact, you might say I owe any success I’ve enjoyed in my teaching career to Ken Voss.

Yet at the time, I hated him.

WHEN I THINK of Mr. Voss, I think of that first interview.

It was probably the longest job interview I’ve ever had. Two hours, if I remember correctly. He talked a lot. He asked a lot of questions, which I answered carefully, my stomach bathed in the raw acid of fear.

I needed this job.

He seemed particularly interested in why I had left my last teaching position.

“You’re saying you weren’t fired?”

Today, this question is illegal. But back then, he had every right to ask. And to be fair to him, my situation was a bit strange.

“Yes.”

“So you spent a year teaching at Central Christian,” he said. “And then — you just resigned?

I nodded, plunging past his skepticism. “I just decided I wasn’t cut out to teach middle school.”

Mr. Voss flipped through my resume. I watched his blank face. He should have been a poker player in Vegas.

Today I know he badly needed to find a competent English teacher, since classes began the following week. Perhaps it had something to do with the low salary he offered.

He eyed me as I sat there, locked into my double-breasted grey suit — hands calloused and tan from working construction under Ohio’s blazing sun.

I had purchased the suit the year before from a High Street tailor when I was riding high during a blissful year in London — escaping my past, rejecting all responsibility — a year before I realized it was possible to take a job for granted, and blow up your teaching career.

“So you weren’t fired.”

Again, I shook my head. He was just doing his due diligence, I told myself.

MR. VOSS’S SUSPICIONS were squarely on target.

Things had gone south in my last teaching position. True, I had been offered a contract for a second year, even signed it. But then — realizing how unhappy I was teaching within that community — I had resigned.

Dumb career move. It’s hard to secure another teaching spot when you’re unemployed. But I was stubborn, and I craved authenticity.

That idealism almost did me in.

Freedom isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. To my surprise, I discovered that my vaunted resume didn’t have the same kick as a year before. That resignation drew questions, not job offers.

By then, I had begun the summer construction job I always worked.

Sweating under the hot sun, pouring concrete and carrying cinder block, I realized how much I missed interacting with my students. The daily grind of construction didn’t compare to the challenges of the classroom.

Not to me, anyway.

SEVERAL WEEKS ROLLED by with no job offers. Seeing an opportunity to lock down a dependable employee, my construction boss offered me a year’s salaried contract. I’d been doing construction with him for 15 years. It was a sure thing.

But then one morning, everything changed.

Usually, I worked on weekdays. But that morning, it was pouring rain, and I found myself in the kitchen of my Canton apartment, sweeping the floor.

Which is when the phone rang.

I picked it up.

“Is this Steven Dinlinger?”

“Denlinger,” I repeated, correcting her automatically.

“Oh, sorry.” Her high, apologetic laugh won my heart.

“This is Mrs. Costello from Catholic Central in Steubenville. I’m the principal’s secretary. He wanted to know if you’d found a job yet?”

I stared at the phone.

“No, I haven’t.”

“Would you like to come down and interview? You have an excellent resume. We desperately need a good high school English teacher.”

What she didn’t say was, “And clearly, you desperately need a job.”

“Sure,” I croaked. “What time should I be there?”

THE TRIP DOWN to Steubenville felt like an epic journey through the hinterlands. State Route 30 was foggy, and for some reason, I ended up going faster than I thought I was going, and just as I saw the exit to Steubenville ahead of me, the flashing lights of a police car lit up my rear view mirror.

When he heard I had an interview scheduled at Catholic Central, he gave me a sympathetic glance. Then he hustled back to his waiting patrol car.

He wasn’t so sympathetic that he let me out of the ticket.

But he was fast enough that I still managed to make the interview on time.

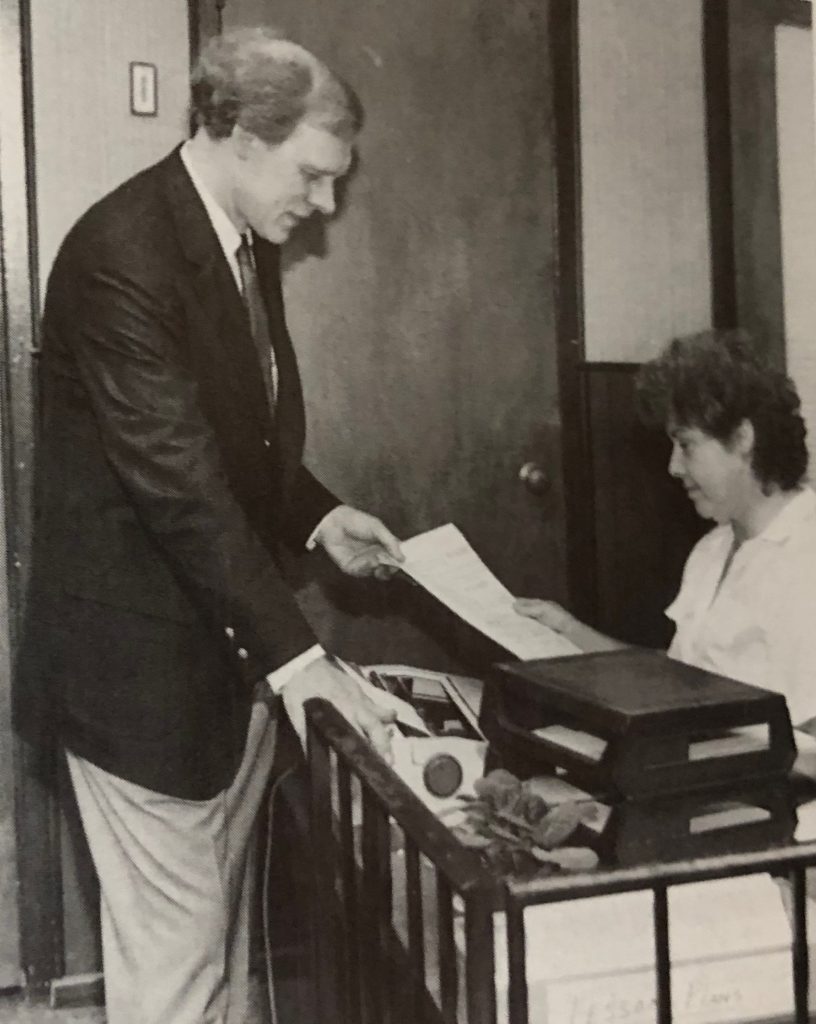

When I opened the door to the main office, Mrs. Costello gave me a warm, maternal smile.

“Did you have any trouble making it down here?”

I wondered if the cop had called ahead.

“Yeah, I was so eager to get here, I got a speeding ticket.”

“Oh,” she confided. “That exit’s a real speed trap. I should have warned you.”

Her consoling smile helped me relax.

NOW AS I sat across from Mr. Voss, I tried to meet his unsparing blue eyes squarely, tried to convince him I was the right candidate.

Tried to convince myself.

He must have made a decision, because he turned to practicalities.

“So you’re living in Canton.”

“I’d be happy to move here.”

“If we hire you, we can help you find an apartment. And you know we’re only able to pay you $14,075 a year?”

It was almost $4,000 less than the contract I had signed and then rejected that spring. But there were no other offers, I reminded myself. It was either this or pushing wheelbarrows around muddy basements — come spring, summer, fall, or winter.

So I nodded.

He stood up.

“I’ll be checking your references. You should hear from me within a day or two.”

Low salary. No job security. I wasn’t even Catholic.

But I hated doing construction work.

BY THE TIME I arrived back in Canton, Mr. Voss had left me a brief message on my answering machine, telling me to call him back ASAP. When I did, he offered me the job on the spot.

I accepted.

School would start in a week, he told me. I’d have to complete the 90-minute commute twice a day between Canton and Steubenville until I found an apartment.

That drive turned out to be a thing of wonder, a passage of inspiration.

Leaving at 5 a.m., I’d drive down Interstate 77 and stop for a large cup of McDonald’s hi-test coffee, then catch State Route 250 toward the Ohio Valley under the rising sun. As I listened to NPR’s Morning Edition, my tan Nissan cut through a maze of lakes, the morning fog morphing into clear sunlight. By the time I rolled up the school’s long drive, I would be wired on coffee.

I’d go to trainings during the day, then check out apartments. On Labor Day weekend, I moved into a small, basement apartment in the nearby village of Wintersville, located among scattered bars and drooping houses.

Once again, I was employed as a teacher. This time I would be teaching high school.

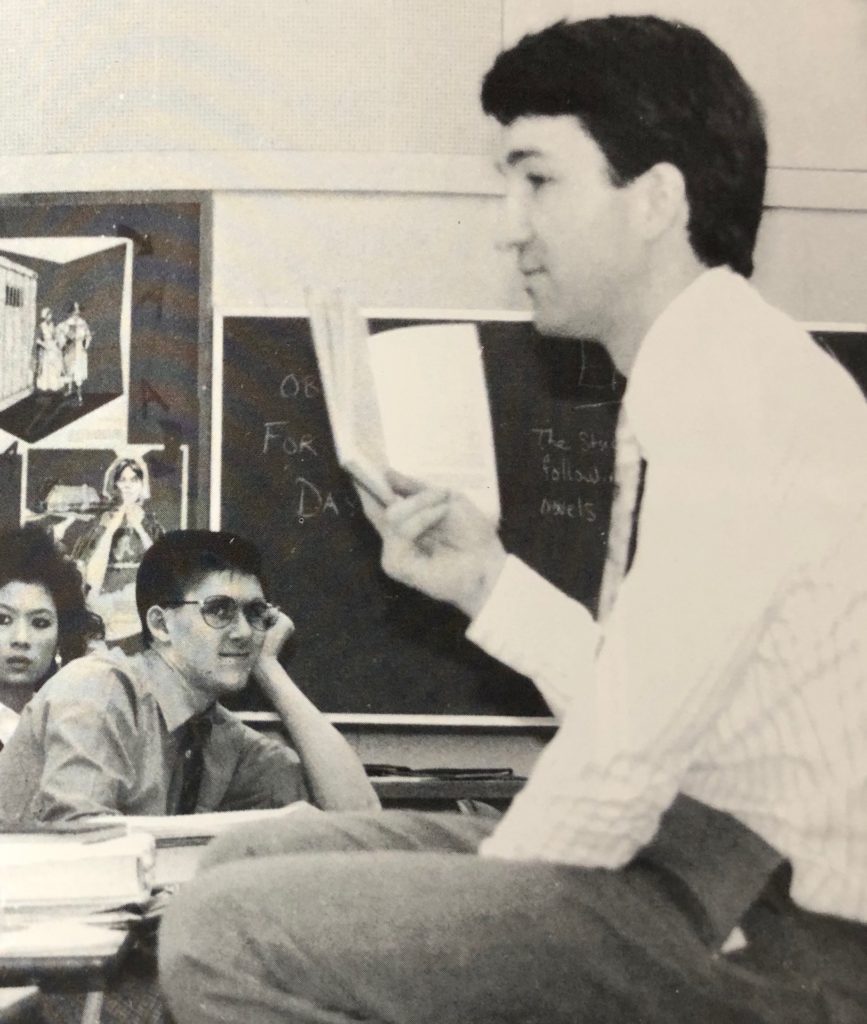

ONCE AGAIN, I was doing what I had been born to do. The pain of the last year had helped me locate my core.

I quickly realized that my new principal took his job seriously. The previous year, my principal’s observations had been sporadic, ineffectual. In fact, he had only observed me after he received parent and student complaints in May.

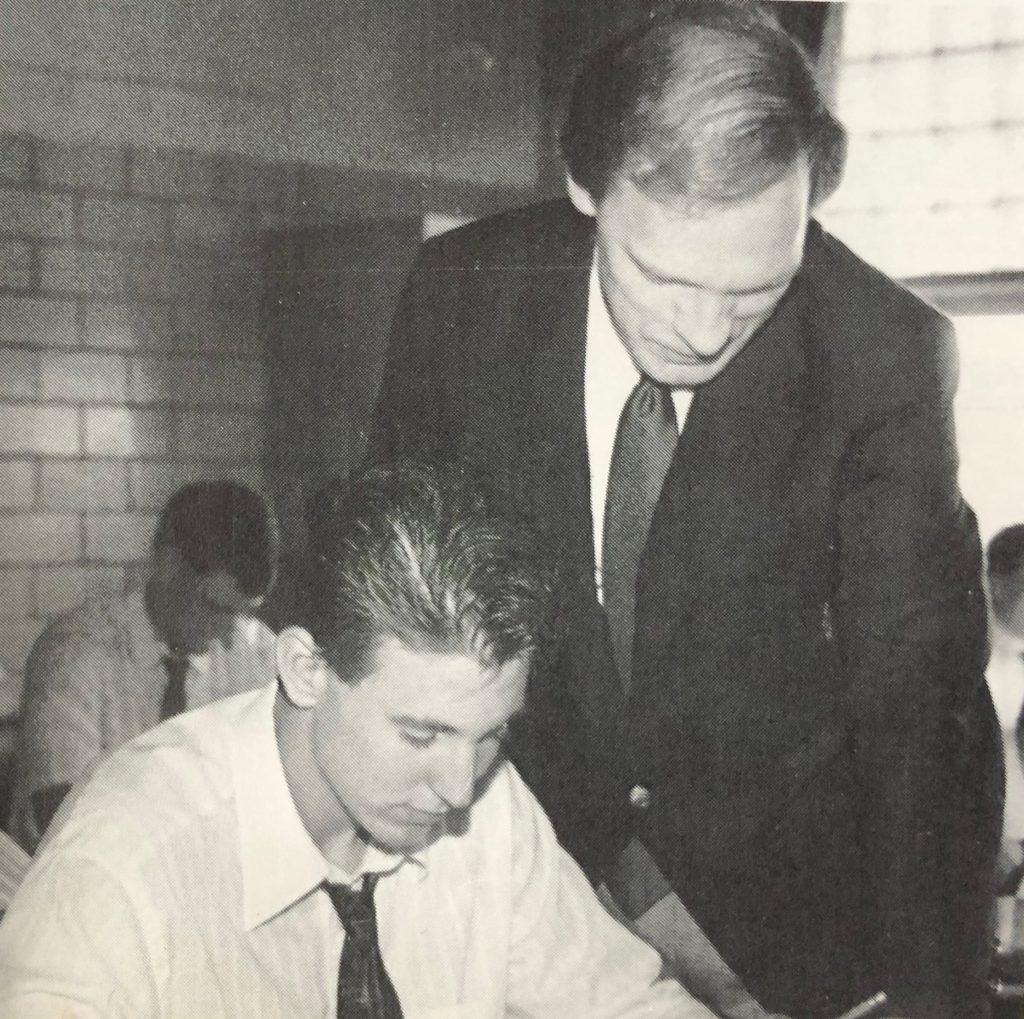

So it was a surprise — and a bit unnerving — when I discovered that Mr. Voss didn’t intend to let me settle in. He showed up the first week, and from then on, whenever he wished.

Apparently, he wished to observe me quite often. I counted 14 observations that first year, most of them brief, but some lasted the entire class period.

Even today, I am astonished by that number. I have colleagues whose administrators can’t find time to squeeze in one visit a year. While teaching at The Archer School, I taught for several years without receiving a single visit from a supervisor. So today, I know Mr. Voss’s behavior was unusual.

In fact, the number of visits he made became a joke in the teacher’s lunchroom.

“Hey Steven, isn’t it about time for Mr. Voss to show up again? How long’s it been? Three days?”

Other teachers feigned ignorance as to why a principal would visit me that often. None of them had received even close to that number of visits.

Finally, our jaded French teacher let me in on her guess.

“I think he must just like attending your class, Steven.”

I didn’t think so. In one of his observation reports — which was seven paragraphs long, averaging six lines each — he noted the following:

While Mr. Denlinger has become much more cognizant of the importance of such matters as meeting constraints in submitting lesson plans and other required materials; similar sensitivity is recommended in the areas such as enhancing the attractiveness of the classroom through subject and/or seasonal displays and expecting students to exercise a reasonable degree of care for school property by covering textbooks.

I remember one moment when I was sharing with my juniors an anecdote from my life, carefully linking it to a poem we were studying. I was sitting down, focused. Suddenly, I realized that Mr. Voss was sitting in the back of the room. How long, I didn’t know.

It unnerved me.

At other times, as I attended school events or supervised students during assemblies, I sensed him watching me. I didn’t know why. Had my former principal given me a bad report? If so, why did Mr. Voss hire me?

I didn’t know.

Until my previous job, I didn’t realize people could smile at your face, and knife you behind your back. This world was new to me. I had grown up among good-hearted Conservative Mennonite people who actually told you what they thought, both good and bad.

While teaching at Central Christian, I had learned a lot of things the hard way. I had learned that cordiality from your principal was not a vow of eternal friendship. I had learned that you shouldn’t confide some things to your boss.

So now — having barely survived the worst academic year of my life since the hell of my own middle school years — I justly wondered.

What had Mr. Voss heard from my former principal?

But by then I had figured out something else: you can’t just ask your boss a question like that.

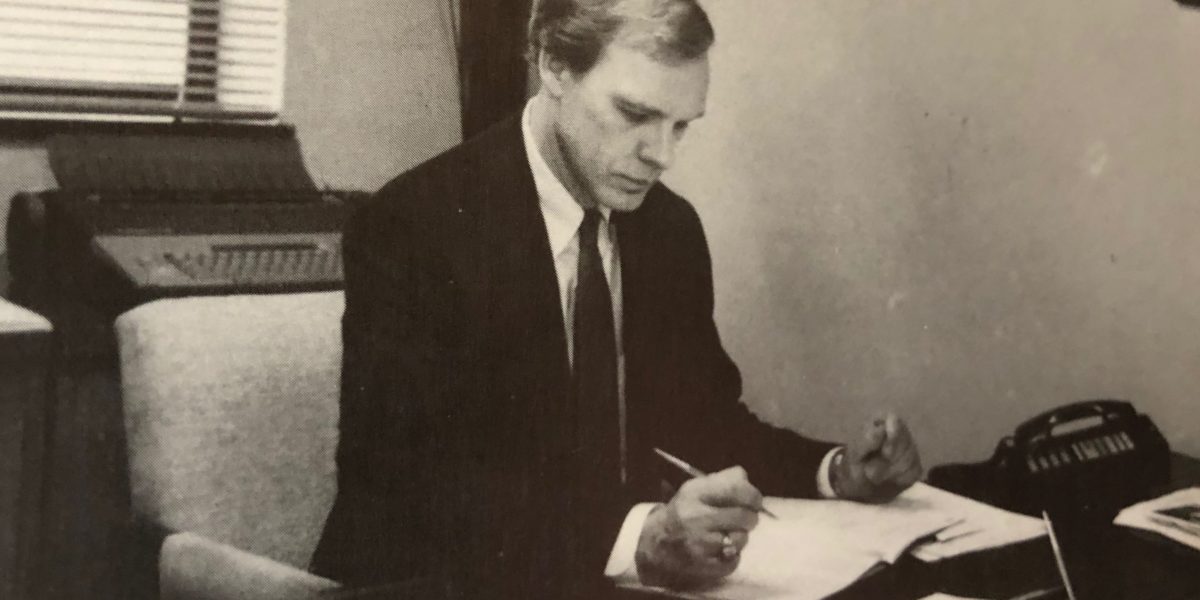

THERE’S ONE MOMENT from my years with Mr. Voss that stands out. It was a moment of pain, more hurtful than anything I had ever faced up until that moment.

It involves a letter I wrote to him.

I mailed the letter to Mr. Voss on June 29, 1991, at the end of my first year of teaching at Catholic Central. I dropped a copy of that letter into a file I labeled “Painful Moments.” Across my teaching career, this is where I’ve put letters I receive from angry parents, disgruntled mentors, hurt students.

I did not read that letter for the next 28 years. Just the thought of it brought back pain. But as I prepared to write this column, I decided I needed to finally read that letter.

Today, even with decades of classroom experience, the pain connected to that letter still hits me full on. It seems impossible, but it’s true.

I know why I waited this long. I know the dread of replaying that pain was powerful. I know I didn’t want to recall the way my stomach roiled, my heart raced, and my greatest fear roared to life.

I didn’t want to remember the way I cringed under the white heat of Mr. Voss’s anger.

That letter was born in a moment of raw fear, in a moment of realization that I had failed. It was a moment I never wish to repeat.

That moment seared me deeply, shaping my professional conscience. The scars it left have made me pause, again and again, before responding to an angry parent.

It was a formative moment in my professional birth as a teacher.

Yet I believe some moments need to be remembered. So to write this column, I decided I needed to go back, endure the pain of remembrance, and re-read that letter.

That letter transformed me.

In fact, I’m convinced that entire experience of pain helped me bridge a gap.

A gap I desperately needed to bridge.

The gap between remaining an amateur and becoming a professional.

Leave a Reply