Stories told by my grandfather about a single leaf taught me to value the simple over the exquisite

By Elizabeth Nussen, guest writer

Looking at the water crashing into a haze of broken droplets and hissing mist hundreds of feet below, I felt nothing.

My boyfriend, Nick, and I had come — as lovers do — to Niagara Falls, chasing after the feeling we were told waited for us here.

The sun roasted the observation deck, and tourists clustered together at the rare spots of shade along the safety rail, the heat of their close bodies blocking the breeze and leaving them as hot and sticky as anyone else. Nick and I had opted for seclusion, letting the breath of the falls cool our fronts while the sun broiled our backs.

It was the summer of 2014, I was 22, and I thought nothing could dim the blaze of euphoria that had enveloped us since we had started dating that spring. Nothing, that is, except nothing.

Imagine, coming all this way, for nothing.

Nothing, at first, but then the hole began to fill with the stale taste of ennui and regret. After a few minutes, these were joined by the hint of anxiety, which climbed steadily higher — from my gut, to my chest, to my throat, to brim at my lower eyelids.

What was wrong with me?

My hand on the observation rail touched Nick’s, with whom I was desperately in love. The trees behind us were blossoming. The sun was shining. The happy chatter of humans and birds filled the air, and an effervescent rainbow curled over the clouds of mist below. Yet there was nothing but the dull ache of boredom inside me.

And then, like light cracking through a cave, the thought of my late grandfather broke into my mind.

“Sometimes,” he said, “I pray, ‘Lord, if I could know everything there is to know about this leaf, I would be content.’”

During one of our summer adventures, when I was about seven years old, my grandfather paused on our walk.

“What is it?” I asked, heart already filling with excitement. He always waited until I asked, to build the moment.

“Do you see that?” He pointed underneath one of the tall evergreens in my front yard.

“The tree?”

“No, beneath it.”

“The pinecones?”

He smiled.

“Go grab one.”

I ran, my bare feet faltering for a moment when the dried pine needles replaced the verdant grass. Ducking under the sappy branches, I spent a few precious moments finding a handsome, whole pinecone, the sort you might find on a wreath or painted silver for a centerpiece. I hurried back.

“Here.” He took it from me and lowered himself down toward the ground, his body a shock of ivory against the green grass with his white sneakers, white pants, white hair and white short-sleeved Oxford shirt, complete with pen and pencil poking out the top of the breast pocket. Despite his German heritage, he looked like a Native American, squatting there, studying the bit of nature caught in his hands. I squatted down beside him, wondering what happened next.

I said nothing. I knew to wait.

“Look,” he said, flipping the pinecone upside down and holding it out to me, pointing to the bracts. “Look here. See that? Count them.”

But he counted for me, elucidating the spirals, decoding creation.

“Do you remember the Fibonacci sequence?” he asked.

“One, one, two, three, five, eight…” I rattled the numbers off.

“Good, now, look, five go this way, eight that way. Go grab another.”

After the third pinecone, I began to wonder if my grandfather understood the torment of pine needles on bare feet and sap in one’s hair, let alone the scratches from the branches, but I kept fetching, amazed that every time the pinecones followed the pattern, just as he said they would.

There will be a tomorrow

when you will have such dreams.

But others will only see

dew on the grass.

~ John Schwarz

More than anything, my grandfather was a man of magic. A child of German immigrants, he had taught himself English by making up his own grammar to write poetry; and he had kept on breaking rules — or rather, inventing new ones — for the rest of his life.

A child of German immigrants, he had taught himself English by making up his own grammar to write poetry; and he had kept on breaking rules–or rather, inventing new ones–for the rest of his life.

It was nothing strange, for him, to teach me about the Golden Ratio and the Fibonacci sequence when I was barely seven years old.

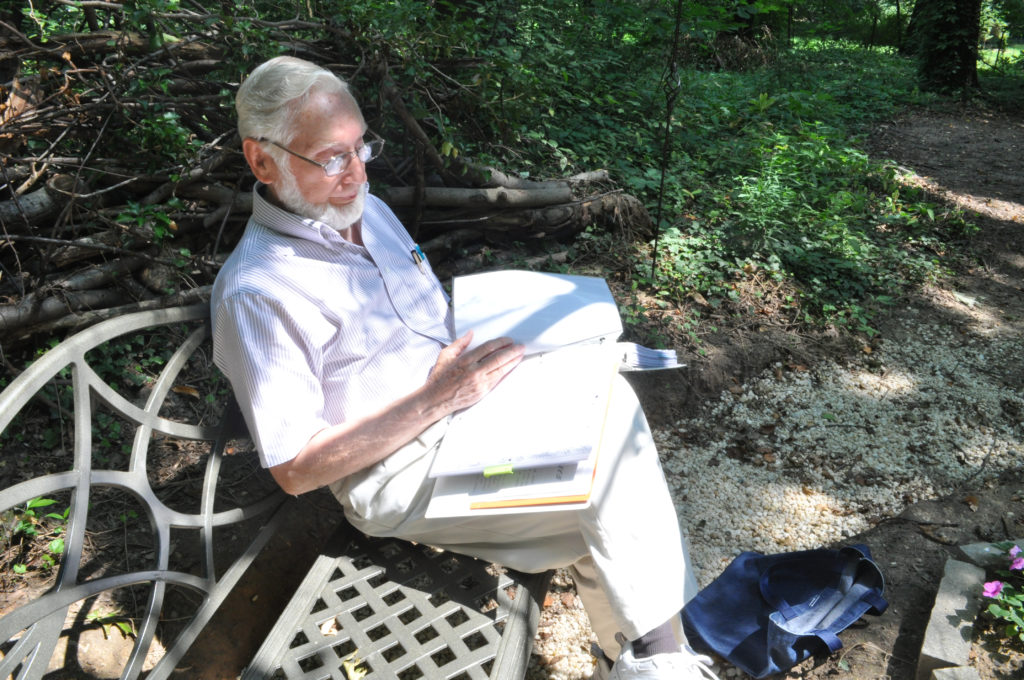

The summer I graduated high-school, we were walking in my backyard. I had my new camera — a graduation gift — and had asked to take his picture while he read his poetry.

He obliged me, easing himself onto the bench in the back corner of the woods and sliding a binder out of his tote bag. With a raspy clearing of his throat, he began to read. I took a few quick pictures but was soon sitting before him, cross-legged on the forest ivy, bugs and leaves tickling my legs.

“There will be a tomorrow, when you will have such dreams,” he finished, “but others will only see dew on the grass.”

“I love that,” I said. “When did you write that?”

Solitude. John Schwarz reflecting in the woods of Elizabeth Nussen’s childhood home in Northeast Ohio. “Looking out the window / I have been watching / the magic of / the tree / dancing / all morning” ~ John Schwarz, from “Pixie Poems.” Photo courtesy of Elizabeth Nussen

“Hmm?” He had been looking at the trees above us, distracted.

“When did you write that poem?”

“Oh. A while back. Your mother was young.”

“I know it’s one of her favorites.”

He said nothing, gazing off into the distance.

“Grampa?”

“Hm?”

“Mom’s told me that poem is one of her favorites.”

“Sure, sure.”

His gaze had remained far off, his thoughts even farther. Feeling awkward, I took a few moments to look through the pictures I had taken, but this only filled a minute of our time. I looked around restlessly.

“Do you want to walk?” I asked.

He agreed, and we strolled, his pensivity unpierced, my perplexity uncured. Where was the garrulous teacher? The story weaver? The magician? This hardly felt like the same man.

Tomorrow

You will see a universe of color

appear at your feet

you will reach down

and pick

rubies

and diamonds

and emeralds

and sapphires

to put into

your jewel box

and treasure forever…

but others…

will only see dew in the grass

~ John Schwarz

A bit abruptly, he stopped walking, his hand reaching out to something he had spied on a tree. I waited with expectation, wondering what treasure he had found. I discovered with disappointment it was an ordinary leaf. But I knew what came next: a story about how this was really a robe for a fairy, or the footprint of a sprite, or an earring that must have slipped from the ear of the Forest Queen. At last he was going to lead me on an adventure.

But his somber mood persisted. He held the leaf close to his eyes.

“Sometimes,” he said, “I pray, ‘Lord, if I could know everything there is to know about this leaf, I would be content.’”

He looked at me, but I didn’t know what to say.

It was just a leaf.

Years later, my now-husband, Nick, and I went to Niagara Falls. He had never been there. I had distant memories of going as a child, but I was ready to brush the dust off them with a fresh visit. During the last twenty minutes of the drive, I could feel my anticipation building.

When we reached the observation area and I stood against the railing, feeling the mist speckling my hands and face, my dominating thought was, “Is this it?” I was filled with disappointment, overwhelmed with how underwhelmed I was. I felt none of the awe and wonder I thought I would feel. Instead, my introverted nature prickled and bristled at the thousands of people swarming around.

Magic. The river in August 2014, a short walk away from Niagara Falls, which the writer visited with her husband Nicholas Nussen. Photo courtesy of Elizabeth Nussen

Nick bent down to my ear so I could hear him over the thundering water.

“Do you want to walk around? It’s a bit crowded.”

“Yes,” I said, relieved. I wondered if he felt unsettled, too.

We slipped away to a glade where we sat for a time, shoes off, quiet.

“We should probably head back,” Nick said. “We came all this way.”

“We’re so lame,” I said.

“Come on.”

He helped me up, and we meandered to the path, following the sound of the falls to find our way back.

On our walk, we came across a gentle river, one that fed into the falls. Nick crossed the bridge automatically, but I lingered behind, staring at the water through a chainlink fence. Backtracking, he gave me a curious look.

“What?” he said.

“Look how beautiful this is.”

“It’s just a river.”

“I know, but…”

But it mesmerized me. The gentle rolls and dips of the water, the rounded beams of light riding on the surface, the tender opposition of the rocks on the banks — it was beautiful. The falls were magnanimous, yes, and I wondered why they had not touched me the way this small river could.

I felt guilty, as if I was being purposefully contrary by shunning the wonder of the crashing waterfalls, the water raging down to its death before being resurrected as mist. Why did this simple path of water captivate me? As Nick had said, it was just a river.

And it was just a leaf.

My grandfather was an art teacher. While other students were only his students for a few years, he knew I was his student forever, and my lessons needed to withstand all the seasons of my life–not just until graduation. Instead of the flashes, bangs and booms of the world, he drew my attention to the quiet settling of the dust that comes after the explosion.

Perhaps that’s why I thought of him that day at Niagara Falls, his memory reaching down to place a calming hand on my shoulder.

It made sense to me now, his fascination with a single leaf. My guilt began to fade. My grandfather had given me permission to love the simple things more than the exquisite; I was allowed to prefer a quiet river over the pounding of Niagara Falls. His lesson in the woods, which at the time had seemed atypical and strange, ultimately held the same kernel as all the others.

The world is full of wonder, and magic.

Especially the simple things.

This is wonderful! You are blessed with amazing memories and treasures from your grandfather.

Yep!

Thanks for sharing, Beth — it was a pleasure for me to read your writing again, as well as to learn from your grandfather’s wisdom again.

I liked this too! Simple things! Like the joy of our fresh mowed yard!