Signing a letter of resignation can feel like signing a death warrant to your relationships

I FIND IT hard to leave people. Take my current situation. Several weeks ago, I sat at my desk, looking at the resignation letter I was about to submit to Vashon Island School District.

I found myself hesitating.

It wasn’t that I was worried about job security — I had already signed a contract to teach at Stafford High School in Fredericksburg, Virginia during the coming year. No, I hesitated because I knew exactly how difficult it would be for me to leave my current high school.

Signing this letter of resignation felt like signing a death warrant — I would be ending relationships I treasured.

My wife often tells me I build community wherever I go. I meet someone, and they feel like a long-lost friend, and we connect intensely, and then … there they go, right out of my life.

How do you deal with that?

Worse, how do you deal with leaving an entire community in which you’ve invested a decade of colorful department meetings with laughing colleagues, steaming cups of coffee with friends on grey and chilly afternoons at the local roasterie, after-school journalism labs with my student journalists, and sun-washed afternoons at eateries with my wife in our little village.

Usually at this point in my column, I introduce a Soul Teacher who has taught me how to do this. It is generally an individual with whom I’ve connected deeply— either literally or in my reading — across years of interaction.

But in this column, I’ve chosen to examine a brief connection — a startling moment when I met someone who imprinted and then disappeared, leaving only a trace of residue.

You can’t really call someone like that a Soul Teacher.

They’re more like a Soul Tutor, someone who in a flash leaves you with a burst of insight.

THE INSIGHT I received came out of a letter I received over 35 years ago. It has guided me during the current challenge I’ve been facing.

I’m about to leave the Pacific Northwest to teach in Northern Virginia. I’m about to leave a community where I’ve taught for the last eight years. I’m about to move away from a place that has deeply affected my life.

For example, I was in the kitchen of our house on the north end of this island when my father called from Ohio to tell me that I no longer have a mother. He followed her to the ground less than three years later. Now I’ve begun to recall things about their lives — and it has changed my perspective.

Take my love for the earth. Here on “The Rock,” as the island is called, I’ve reconnected with my love for the earth. My mother loved planting and nurturing life, and for the first time since childhood, I have reacquainted myself with gardening tools, seedlings, and fertilizer. As I tend it in the early mornings of springtime, I sense her spirit pacing beside me.

But this island can also be an isolating place. It’s the only place I’ve lived where you have to spend three hours to take a ferry across the water just to go to a mall, eat at a McDonalds, or catch a plane to visit your family at Christmas. And if you want to see a show in Seattle, don’t plan on getting home before the wee hours.

In addition, it’s taken time to connect. My students aren’t exactly warm and fuzzy to new teachers, especially to a writer like me who must maintain clear boundaries and an emotional distance between myself and others in order to survive.

So it’s taken me a long time to find my place.

Like their parents, my students have seen many teachers come and go. They know most people lack the commitment to handle the temperamental, isolating nature of an island. Why invest in someone who may not be around a year from now?

But sometimes you don’t have a choice. As in my case, family commitments sometimes leave you no choice but to leave.

So what’s the problem?

THERE IS THE matter of my emotions. I’ve just spent eight years sinking roots into this community, and leaving it is going to tear up those roots.

How do I leave without pain?

The short answer is — it’s impossible.

But as I sat there, looking at the unsigned contract, I recalled another departure, another moment when I needed to leave a school — in fact, it was when I left my first teaching position.

I was 20 years old, and I looked 16 — almost as young as the only senior girl among my remaining 17 students in grades 7-12. Over the past year, I had been thrown into a series of responsibilities any young teacher is forced to confront while teaching at a small Conservative Mennonite school.

At the beginning of the year, I had been hired as principal and teacher with no experience and barely a high school diploma (and yes, many conservative Christian communities still hire young people like that to educate their children).

Now after a year of teaching, I had been invited to return home to teach at my alma mater in Hartville, Ohio. I couldn’t resist such an offer. So I had let the school board know I wouldn’t be returning the following year.

I was feeling the same excitement I am feeling now.

One in particular, Glendon Yoder, was destined to be my lifelong friend. I had sung at his wedding several months before, and he would eventually stand up with me at my own wedding 28 years later. He was the son of the pastor who hired me — and a rebel.

BUT ALONG WITH that excitement came a burst of pain — one I didn’t expect.I had taken my job seriously, and had connected deeply with my students. At 20 years old, I was also part of the youth group many of my students attended. I had made rich friendships with other young people my age.

Back then, we spent hours talking after youth group activities, standing outside in the cool air beside his brown-and-cream Silverado pickup, telling each other stories about our brushes with hypocrisy and the abuse of religious authority we had both seen since childhood. I played Rook with him and his brothers until late at night — I suppose card-playing of any kind was a risque thing to do in that community, even if our drinks were just Pepsi.

Glendon and his three brothers teased me, accepted my eccentricities, and took me in.

As a teacher, I took my students on chaperoned camping trips, even fished with them. I read books to them. We had wonderful discussions. I cared about them, cared about changing their lives, cared about seeing them succeed. All this with only a high school diploma from the parochial school where I had been educated.

During a trip home for vacation in February, I was approached by the school board chairman of my alma mater. Having heard about my teaching, they now wanted to hire me to teach.

I couldn’t resist the offer. By then, I was homesick.

But I did realize that leaving was going to be hard. I had bonded with my new community of friends.

Leaving would have been even more difficult had I realized how decisive that departure would be. Except for Glendon, I would fall out of contact with every single friend I made there for over two decades (until the advent of Facebook reconnected me with numerous past students).

I didn’t realize how completely I would lose contact, but I did know I was making a dramatic shift in my life.

I remember her as one of the older ladies in our church, quiet during the services, but always smiling, her wizened face peering out of the large white bonnet that mostly covered her thinning brown hair.

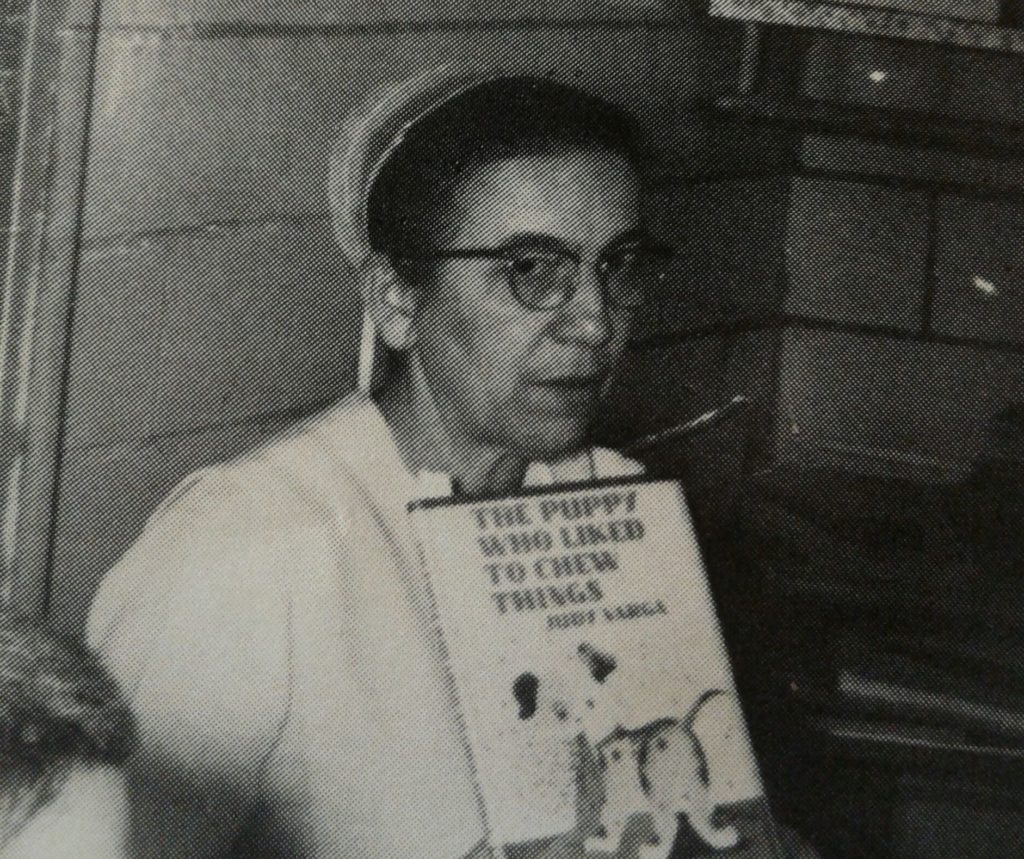

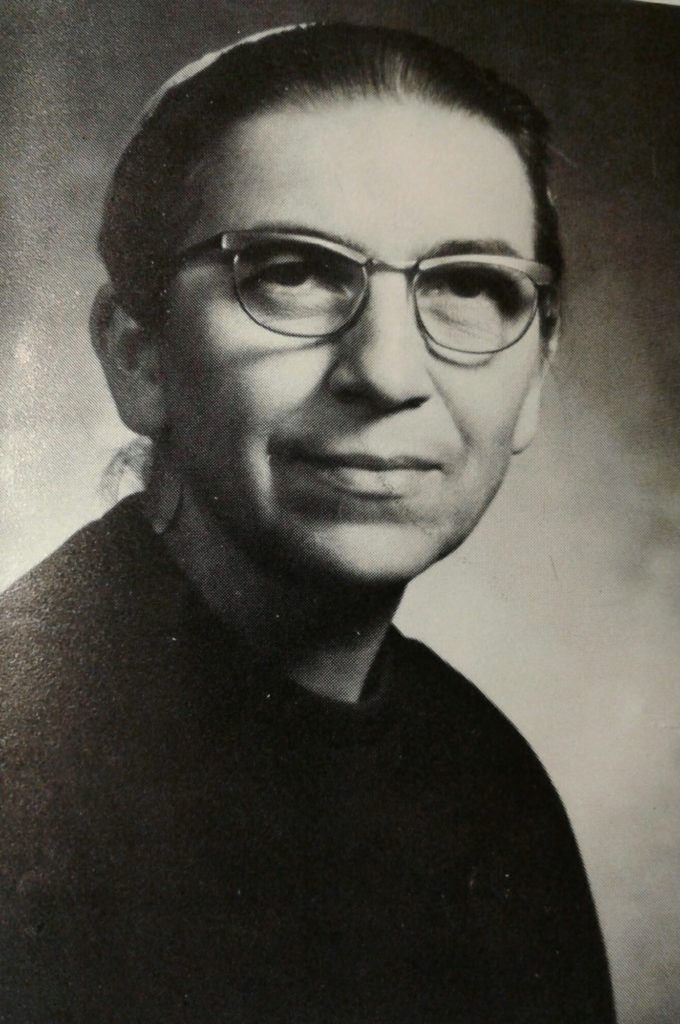

WHAT GOT ME through that departure was a letter I received from Sister Elizabeth Gingerich, a teacher from my alma mater. I didn’t know her well — in fact, that letter is the only conversation I remember having with her.

But she remembered me, probably because she had become a dear mentor to my sister Rosey, who had probably talked to her about my pending departure, and my worries about it.

It was a letter that came out of nowhere — and unfortunately, it’s one I didn’t bother keeping. But I do recall its message. I remember reading it, standing by the mailbox in the clear winter air Phoenix enjoyed, reading her words scripted carefully on cream stationary.

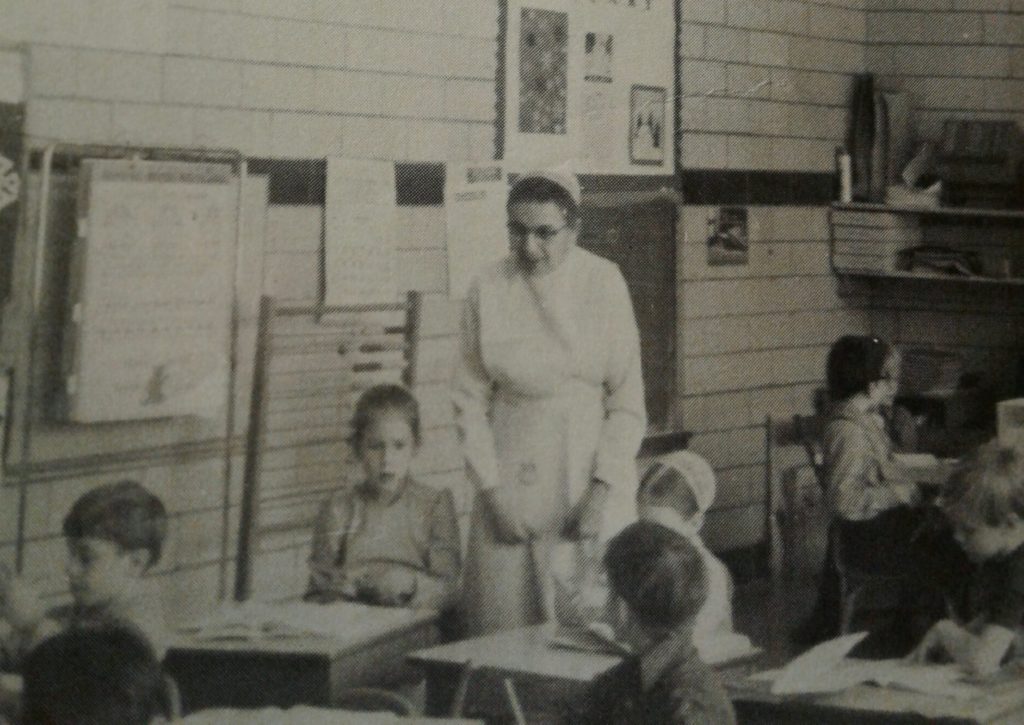

She was finishing up her day of teaching, she wrote, and she was thinking and praying about me. She imagined my decision was a difficult one because she had made similar decisions — for example, when she left her mission post in Germany to return home and teach first graders.

Although it was difficult to leave students you love, she said, I needed to be practical. Students go out into the world without you — that’s the nature of teaching.

TODAY, AS I recall that letter, I am filled with wonder. I barely knew Sister Gingerich. How did she know I needed that kind of wise encouragement? Teachers are busy folk. What made her take time out of her schedule to communicate with me?

She knew about me, and during my first year of teaching in Phoenix, she had been praying for me. When she heard I would be coming home to teach — becoming a fellow faculty member — she had decided to sit down and pen an encouraging letter.

Elizabeth was not particularly outgoing. She was friendly enough, but she limited her energy to serving her students. I remember her as one of the older ladies in our church, quiet during the services, but always smiling, her wizened face peering out of the large white bonnet that mostly covered her thinning brown hair.

She had never been my first-grade teacher, but she had taught many of my siblings. Her classroom discipline depended upon her kindness and her meticulous approach to all of her work.

My sister Rosey remembers the precision Elizabeth demanded, the importance of concrete instructions.

“The first year she taught,” Rosey recalled, Elizabeth had both the “first and second grades with a total of 60 students. The reason she could do this was her discipline. She would have the students walk a straight line by following the square tiles on the floor.”

Rosey recalls Elizabeth’s perfectionism, and her beautiful handwriting. Her frugality.

“She taught me to save everything,” Rosey said. “Every used envelope was carefully taken apart and used for notes. Plastic bags were carefully folded into [one-inch] squares.”

Elizabeth didn’t waste time either. “She had knitting, crocheting, or something good to read close by,” Rosey recalled.

I DON’T REMEMBER responding to Elizabeth’s letter. I don’t remember her passing several years ago. I don’t even remember writing her to thank her.

But that letter — it’s one I often reflect on during times of transition.

Like now.

Because it would be hard to ignore the last six years I’ve spent working with journalism students on Vashon Island. This island knows how to provide nurture and talent for young writers and artists.

In fact, people say there are only three kinds of professionals on this island — artists, lawyers, and teachers. Not quite true, but close. So kids grow up valuing art and learning to write. By the time I get them, I just need to teach them the basics of journalistic writing, and they can take it from there. The hardest job I’ve had to accomplish is giving them structure and keeping out of their way.

The community supports their work — heart and soul. Here everyone knows each other. Here many of my students have been together since nursery school. Here they share an unspoken language.

Becoming part of the community means I’ve worked with some of my senior editors since their freshman year. I’ve taught their siblings. For example, my editor-in-chief is the sister of a student I coached in musical theatre. The sister of one of my sophomores was last year’s copy editor. Last year’s sports editor was the sister of the publishing editor.

This sounds as tangled as the familial networks of my childhood community.

It’s not something you easily toss aside.

Yet that’s what will happen. By leaving this job, I will cut myself off from this community. To ensure that I don’t undermine the adviser who takes my place, I will discourage students from writing for my “advice.” When college students come home to visit Vashon High School, I won’t be there. I’ll no longer run into former students when having dinner with my wife, or stopping for an ice cream cone at the local coffee shop.

This doesn’t even take into account the relationships I’ve built with colleagues.

“Leaving them doesn’t mean you don’t care, and it doesn’t mean you’re a bad teacher.”

from a letter by Sister Elizabeth Gingerich

For example, I have coffee three times a week with two former teachers. They “get” me, which is something I value. I feel comfortable being myself with them. We brainstorm teaching ideas and ransack our memories for teaching stories. We analyze politics. They give me advice about decisions I need to make.

Neither is much of a phone person. And there’s going to be a three-hour time change separating us.

Transferring to a new school means having to embrace a new community, and because Stafford High School is familiar with transient teachers — after all, they live near D.C., where people come and go depending on what Uncle Sam asks of them — I will most likely face skepticism when I arrive there, too.

As I arrive, I know what they’ll be thinking: “How long will he stick around?”

In light of this, how wise is it to leave, just when I’m becoming an integral part of this little island community?

So now as I struggle, I remember again that letter Sister Elizabeth wrote.

I REMEMBER THE central paragraph.

“I can imagine you’re struggling right now with feelings of guilt: How can you leave your students after you’ve poured your life into theirs over the past year?

“I understand this feeling well. This leaving is always difficult. But if it weren’t, you wouldn’t be the caring teacher I know you are.

“So I’ve written to encourage you as you leave. Remember, you will have many students across your teaching career. They will leave you, and you will leave them. That’s part of life. You must look forward, rather than back. Your students will have other teachers, and they will love them as well.

“Leaving them doesn’t mean you don’t care, and it doesn’t mean you’re a bad teacher.

“This is the practical side of teaching. The key is that while you worked with them, you served the Lord by doing the best job you could.”

THAT WAS THE wisdom I needed at that moment. Hers was the letter I needed to read. The message still rings across the decades.

Elizabeth understood the cycle of grief a teacher experiences when working with students.

It’s something I have come to know intimately across my career.

For example, I dread going to high school graduations because of the finality, the funereal feeling of emptiness after the graduation ceremony — as my students are encircled by their families, leaving me shut out as my formal role in their lives ends, as I see how unimportant I am — now merely a class title and grade on the student’s transcript.

There is the embedded sense I’ve lost something of great value, that I no longer matter in their lives, really. I taste the bitter reality that they’ve moved on — and that the relationship between us as I have known it is finished. My task is over. I have given them everything I could, and something has changed — permanently.

It’s something we teachers go through each year, sometimes each semester.

For a season, we have these lives to mold, these minds and intellects to challenge. And then they’re gone, and without ceremony or formal grief we must move on, called in our vocation to work with the next crop of students we are given.

Time is fleeting — especially the time we have with those we serve.

THE EXPERIENCE OF writing and submitting that resignation letter to the Vashon Island School District seemed so final. And it is.

Our lives will now move inevitably apart.

I’m an optimist, of course. I hope to maintain the friendships I’ve made — I have a track record of being persistent with the phone and email. There’s also a good possibility we’ll return to the area when my wife finishes her PhD. But I also embrace the reality of this move.

Distance separates friendships.

So as I reached to sign the resignation letter before me — what helped me through that moment was the memory of a little, wizened teacher with sparkling black eyes who loved her students deeply.

She was a true Soul Tutor for me —someone who taught me that this uncertainty, this constant state of transition, is the life of a teacher.

If you like what you are reading, please follow our Soul Teachers website and “Like” us on Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn. Or you can reach me at StevenDenlinger@thesoulteachers.com. The first six episodes of our Soul Teachers podcast, which I host, are in post-production and will soon begin airing weekly.

Nicely done. Enjoy your new adventure.

Thanks, Mike. I hope we do. Good to hear from you.

Hey Steven,

For what it’s worth, Elizabeth started teaching school the year I

went to third grade. My two younger siblings had her for first and second grade and

both of them love to read like I never did. I found out later that Elizabeth so

loved reading that most every one of her students inherited a love for reading also.

And when it came to expression, she had the whole class quoting a story with such expression,

that I can still remember phrases and the whole story to this day.

Tim

remember to this day

That’s really wonderful, Tim. That’s a wonderful memory for you.

I loved this! Love to you as you transition! Your little sis, Heidi

Yes, Heidi. Just think: we’ll be much closer.

The beauty of social media is being able to stay connect–or reconnect–with former students! I find great joy in continuing to relate on Facebook to some of the now-adults I taught as fifth graders between 1981 and 2005. I hope you can do the same!