Taken from “10 Secrets To Empowering Teen Leaders,” this one focuses on building self-confidence

If you intend to get the best work out of your teen leader, you need to learn how to praise.

Again, I turn to theatre director William Ball. In A Sense of Direction: Some Thoughts on the Art of Directing, he argues that a director must constantly praise those who work with them. You want the actor to depend on your praise, he says. It’s a way to get the actor to consistently work hard and offer their best ideas.

I first applied this in directing high school theatre, dutifully following Ball’s instructions.

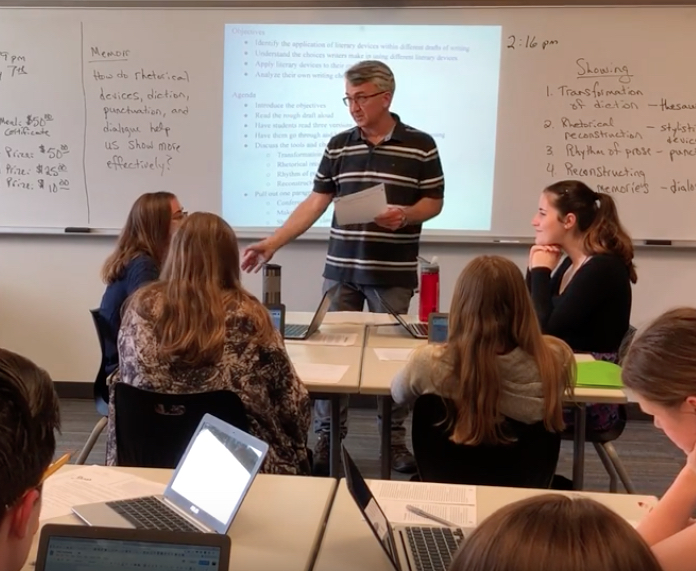

But eventually, it reshaped my style of teaching, as well — well after I had left teaching theatre.

In fact, praise should be your dominant trait when teaching teens.

By the way, don’t expect that students will thank you for your praise. They may even seem uncomfortable at first.

But keep doing it until they expect it.

I saw the power of praise work most clearly in the teaching of my own theatre teacher at The Bread Loaf School of English. Back then, he was the director of Trinity Repertory Theatre and one of our instructors.

Today, Oskar Eustis is one of America’s finest directors and a mentor to some of our greatest playwrights.

Eustis is best known for having nurtured Tony Kushner as an struggling playwright. Eventually, he commissioned Kushner’s Angels in America, which went on to win the Pulitzer Prize for literature.

Today, Eustis is the director of the Joseph Papp Public Theatre in NYC. You might argue he’s the dean of American theatre.

I saw Eustis follow Ball’s advice most clearly when he was teaching me during my graduate years at Middlebury College in 1997-98, where I took three classes with him: Dramaturgy, Modern American Drama, and Three Theatrical Styles.

As part of his teaching, Eustis brought to Bread Loaf his company of actors from Rhode Island’s Trinity Repertory Theatre. They were paid as artists-in-residence on our college campus, so they they were always available to the instructors.

The group would prepare and perform the scenes we were studying, and Oskar would watch them carefully, his face riveted on them as they performed, and alive with interest and joy. Afterwards, he praised them, individually, specifically, and effusively.

There’s a reason Eustis’s actors poured their hearts into their work.

Watching him interact with his actors, I decided I wanted to practice the same skills. I wanted to see my theatre students perform in the same way with the same level of intensity.

Eventually, I figured out the same skill worked with all of my students. It isn’t just actors or acting students who need that kind of praise: everyone does if you expect to infect them with your enthusiasm.

When I first began the shift to praise, I was still following what I had learned from my own teachers: the fine art of sarcasm. At some point in my career, I had come to believe that my students found me funny — my classroom was full of laughter! — when I made smart-ass remarks.

“Mr. Talbot,” I would shoot at the student who arrived late. “Did we decide to spend an extra hour in bed? That movie last night must have been something.”

“Miss Miller,” I would fire at the student who was whispering to her peer. “Did you wish to share with the rest of us, as well, about the details of last night’s party? Wait. (dramatic pause.) We’re not actually interested.”

It was all such loads of fun.

But as the years wore on, I grew tired of the fallout I incurred with my ripping humor. I learned to dread the occasional, angry phone call I received from parents. I learned that having to meet with an unhappy administrators made those moments less … special. I learned that apologizing to students who “didn’t catch” my dry humor really sucks.

Besides, as a friend assured me, “You’re not very good at being mean.”

I eventually realized that in this respect I was very much like my father: he was at his best when he was kind, rather than angry and sarcastic.

Slowly but surely, I began to strain out the sarcasm from teaching style. The amusement I received wasn’t worth the pain. Somewhere along the way, it also dawned on me that you can’t consider yourself funny just because your students laugh.

Student laughter can be mean — it can hurt. It isn’t a gauge of effective humor.

Over the years, I have learned two basic rules for applying praise.

First, your praise must be honest and specific. General comments — “Good work, class! Great job, Johnny!” — don’t count. Praise only makes an impact when it is based on careful, patient observation. You observe carefully and praise specifically. You need to notice very small, nuanced things, and recognize them publicly.

Second, your praise must come from an authentic place. This isn’t the time to be cool. This is the time to notice what a student is doing right, and describe that specifically and enthusiastically, encouraging the students to continue that behavior.

This praise should not be for things the student is born with: talent, beauty, creativity. Your praise should focus on skills the student has struggled to master, and is finding success in doing.

According to my students, “Perhaps above any other quality, Denlinger praised initiative. This was the foundation of his teaching style: encouraging students to be able to thrive without him. His students have clearly begun to reflect the philosophy.”

If you praise a certain behavior, your students will give you more of it.

Telling a student they are smart or talented only makes a student’s head swell. It ruins the student’s initiative because they haven’t earned the praise: it was a card Nature handed them at birth.

Praising a student’s actions — something they can control — will transform the culture of a classroom.

And make this praise effusive. Make sure your students know you’re happy.

In fact, Ball argues that you should embarrass your actors with praise. Point out when they are doing the right things. They may duck their head and flush with embarrassment, but when they see you’re doing the same thing to others, and when other students are also praised, it will become part of the culture.

There’s another reason praise is important to teaching. It’s based on our need for attention.

I learned this from another mentor, whom I’ve written about in a previous column: Alice Aspen March.

March has argued in her teaching and writing that most psychological and emotional issues we face stem from a lack of attention. She argues that it’s the missing ingredient in failing relationships. She traces the origin of her interest in attention to her own experience of trying to raise a child who was struggling to succeed in school, and suddenly realizing what she had failed to give him.

“What he needed was attention,” Alice told me.

By praising your students, by pointing out what they are doing right — you are fulfilling their inherent need for attention.

But most important, by praising constantly — and teaching your leaders they must do the same thing to those they lead — you are shaping a culture of generosity and praise. Everyone feels happy when praised, and when people are happy, they are more successful.

There’s a final reason I believe honest, authentic praise is important. I’ve seen it in action.

Of all the places I’ve taught, the most effective school culture I’ve observed existed at Hoover High School in North Canton, Ohio, where I was the drama director and yearbook adviser.

It was a culture in which teachers and administrators were expected to express their appreciation through notes of praise. When I put out a yearbook or produced a show, appreciative notes found their way to my mailbox. I even received notes of praise for my teaching. Other teachers had the same experience.

Praise was a habit that everyone was expected to practice.

Perhaps that expectation was set by my first principal there, Ted Isue. He was a former principal who spoke little but listened well and smiled a lot. A former French teacher, Mr. Isue cared so much for his teachers that he read every single one of their mid-term narrative reports, correcting any spelling or punctuation errors.

He also praised often.

After seeing a show I directed, or watching the yearbook come out, most of the administrators took the time to sit down and pen a note on a small card.

Those notes came out of an authentic place: they showed my supervisors had paid attention to whatever they were praising. The notes meant something because the writers talked specifically about what they liked. It wasn’t a general note sent to all the faculty telling how “awesome” we were.

It didn’t surprise me at all to find that the school district continues to receive top marks among Ohio high schools. The habits of praise and attention I gained while teaching there changed the way I teach and learn.

Recently, I received a card of thanks from a student who took a class with me this past semester. Amidst her comments, two sentences stood out.

Until I was in your class, I had never met anyone who has always seen the best version of me, even when I don’t see it myself. Thank you for pushing me to the limits of my comfort zone and beyond to help me become a better student of literature and life.

~ Thank You Note to Steven Denlinger, 2019

Making praise part of your pedagogical style — learning how to notice what your students are doing right, and showing them what they are doing right through your praise — is a crucial part of transforming your students into highly effective leaders.

Most important, it transforms the classroom into a place where students love to attend.

Next week — Secret #3: Teach your leaders it is their responsibility to give back to the community.

Leave a Reply