He was our teacher, sometimes our friend, but most importantly, he modeled the way we should approach life

I heard about it afterward.

I heard about the way our high school principal and teacher broke down in tears during his speech. I heard about the way he offered an apology for his mistakes.

“I mean, I was still a college student when I started teaching,” Myrrl Byler said. “Some of you might have thought I was a hard teacher? I was just teaching you what I was learning in college. I thought that was okay.”

I heard sympathetic murmurs. In the back of the darkened church auditorium where we were meeting for our class reunion, I leaned forward.

A little context.

Technically, this wasn’t a class reunion, since 21 classes were invited to our tiny little parochial school to celebrate their education within this Conservative Mennonite high school. We met at the small church in Hartville, OH, that founded the school in 1956.

It was the school where my seven siblings and I had each earned our high school diploma. Four of us were in attendance, along with approximately 250 other former students. It was the sort of reunion where there are religious devotionals and carry-in dinners and a cappella music.

Brother Byler (as we called him back in the day), was reflecting on his experiences as a teacher and principal from 1975 – 1981. Today, he’s the director of an educational program based in Harrisburg, VA, that oversees teacher exchanges between Mennonite colleges and church partners in China.

But today, he was just Myrrl, talking to former classmates and students.

Above him on the screen was a photo of a long-time employee, someone we all knew, someone we students had often teased — and not kindly. Myrrl spoke of the way he himself had failed to give the right kind of attention to employees or students with special needs.

He talked about teasing students when they made mistakes or failed a quiz.

“That’s what we did back then,” he said. “Today, I wish things were different. I’m sorry about that.”

Imagine that, a person in authority, saying he was sorry.

My former principal and English teacher wasn’t in front of a judge, he wasn’t being forced to apologize in order to get a lighter sentence — in fact, he’d done nothing more than most of his peers had done almost 40 years ago as an educator.

I grew up watching other teachers humiliate or punish students when they failed. And I made the same mistakes when I began teaching in a parochial school at the age of 20.

So for me, the moment was electrifying.

Apparently, I wasn’t the only one. Afterward, one of my classmates spoke to me in wonder, awe inflecting his voice.

“I’ve never seen anything like that before,” he said, shaking his head.

I hadn’t either.

It was a promising start — people in authority admitting they did wrong. I wondered how many of my own teaching mistakes I should go back and confess to former students.

There would be plenty.

I remember the absolute fear I had for my teachers throughout elementary school, when a teacher could pull you in front of the class and use a two-foot, two-inch-thick piece of oak or walnut, and slam it against your behind, again and again, eliciting screams and tears.

I remember one such event in which the teacher landed sixteen cracks — striking with full force. I was a young fifth-grader who cried easily, who was the smallest boy in class, and who was teased by my classmates with the pejorative “Stevie.”

A bookworm who hated athletics, I had been caught bringing comic books to school, which I shared with two classmates.

Actually, they grabbed them from me.

Comic books about Batman and Wonder Woman — they were the devil’s instrument, we were told. Before he administered the blistering paddling, my teacher informed me soberly that I had been the leader, and thus must be punished twice as hard.

In no universe — real or imagined — would I have been considered a leader. I was tiny, scrawny, the kid they chose last when playing softball or basketball at recess, and then, only under duress.

It must have hurt him just as much, that teacher, having to paddle me.

It must have hurt like hell — all 16 cracks.

By the time Myrrl Byler began teaching me in seventh grade, I had shut down. I attended school only because I had no choice.

I read books in which the protagonist ran away from home, novels like My Side of the Mountain. Turning in homework was a rarity. I often got caught reading in class.

But instead of beating me to get my attention, Myrrl did something unusual. He pulled me out of study halls — took the time to talk to me. He asked me questions, tried to get inside my head.

Why didn’t I study?

He even talked to my older sister — who was by then teaching with him — asking about me, trying to figure out what motivated me.

For two years, he worked to reach me. For two years, I ignored him, refusing to take him seriously. For two years, my grades steadily dropped lower and lower.

Eventually, that’s when I failed three subjects (including English).

I woke up — frightened of being a social pariah.

Having gotten my attention, Myrrl proceeded to pass me on probation into the ninth grade — extending a trust I hadn’t earned. My high Stanford Achievement Test scores proved that I had the ability to succeed.

Previous teachers had believed otherwise.

Only Myrrl had the faith to believe his intuition.

To everyone’s amazement, I bought into his vision of me. I did my homework. I began to make friends.

And my grades began to improve.

But just because the past is history doesn’t mean it disappears. It stays there with you and makes you question yourself.

It eats at the soul.

And so I never forgot the injustice I experienced in my elementary years, the isolation to which I retreated in my middle school years — and the teachers who used physical abuse to exert absolute control.

Myrrl himself had graduated from Hartville Christian High School several years before he began teaching us. When he graduated, he followed his peers into the construction trades. He tried carpenter work

One day under the blazing Ohio sun, he decided he needed to do something different. When the school board asked him to teach at Hartville Christian, he agreed.

Our class was his first assignment, and we imprinted on him, hard.

Over the six years of his teaching, he followed us, continuing to teach our English classes as he got his B.A. and then his M.A. He was also our Physical Education teacher and our class adviser.

There were times when he and his wife Ruthie, who also taught elementary school, invited our class over to their home. There we talked about what mattered to us. We could be honest with him.

I never thought he was very impressed with me, even as my grades rose and I went from being a failing student coming out of middle school to the top half of my class my senior year.

I desperately wanted his approval.

I remember going to him early one morning after I finally got a poem published in a national collection of high school poetry. He was in his office. I was a junior in high school — he was by then the principal.

On the wall, the three-foot paddle everyone called “The Oar” was collecting dust. Unlike his immediate predecessors, he didn’t use it.

He glanced at the congratulatory letter, nodded, and handed it back to me.

“Good work,” he said. “You should be impressed with yourself.”

It wasn’t quite what I wanted to hear. I wanted something more, some moment in which he recognized everything that had happened, perhaps.

But later, he took the time to compliment me in front of the class.

They clapped.

It was enough that from then on, I considered myself a writer.

Myrrl had the courage to be honest with us, to tell us about what it was like to be a college student — this in a community that found higher education suspect.

He told up about his screwups. He described the professors he loved. He reeled off witty jokes about political figures. We knew he wasn’t sharing these stories with the other classes he taught because we all talked — and they told us he didn’t tell them anything.

It made us feel special.

Somehow he passed on to us that he had high hopes for us, that he believed we would do something important in the world, that he thought we all had a destiny. In response, we decided no one could be as good a teacher as Myrrl.

In other words, we were the kind of brats no other teacher wanted to teach. I discovered this because other students told me later, well after I graduated. “We hated him,” one student told me. “We felt excluded.”

Our class felt very much included.

Other teachers also resented us. I discovered this when I returned to my alma mater in 1984 to teach — only three years after I graduated from high school — following in Myrrl’s footsteps as an English teacher.

“Your class was hard to control,” they told me. “The only teacher you all would listen to was Myrrl.”

To our class, this was not an insult. We knew we were difficult — and we were proud of our rebel status.

We were a one-teacher class.

I didn’t have the same relationship with Myrrl the other boys in my class did. They were all part of the bro culture of athletes, and I was definitely not a bro.

Instead, it was through our mutual love of literature and the discussions he led about poetry and novels, where I saw the expansive nature of his soul. I learned to love writing under his astute observations and acerbic insights. During the few times he praised my work, I felt a soul connection.

I loved his Socratic teaching style — the difficult books he assigned.

Yes, on some level we were all aware that Myrrl didn’t have much time to give feedback. It was a joke among us when two boys in the same class turned in the same assignment. One of them got an A, the other a C. For some reason, we understood.

At least I did.

I didn’t know Myrrl was emulating his own favorite professors in college. Years later, when I wrote for Soul Teachers about my favorite professor, Dale King, Myrrl wrote and informed me that I was uniquely prepared to love him.

Everything Myrrl taught us came straight from Mr. King’s English classes.

Perhaps one of the reasons we connected with Myrrl was because, like us, he was a rebel within our community.

It was from Myrrl that I learned the foundation of a liberal education: Truth is found through asking questions. So he refused to indoctrinate us — as the school’s teacher handbook required. Instead, he encouraged us to ask questions.

Myrrl modeled this. He wasn’t afraid to question anything, especially the traditions within our community. He questioned the way women were treated. He questioned the literalistic approach to the Bible. He questioned the meaning of our lives.

And by doing so, he infected us with the same quest.

During the many class discussions we had with him, Myrrl gave us a glimpse of what it was like to live a meaningful life outside our culture.

It inspired us.

This inspiration connected us to him, and it laid the foundation for a true friendship. It was a friendship because Myrrl refused to use authority as a weapon. He treated us like adults l. He offered us respect. He gave us our autonomy. And thus, we came to share his values.

By the time we reached tenth grade — when students begin to see their teachers as people, not just caricatures — the bond between us was unbreakable.

Class chemistry and personality is an odd thing of chance that experienced teachers recognize. Each class period contains a blend of personalities that together comprise something greater than the sum of its parts.

As a teacher, I can point to certain cohorts I’ve enjoyed most. With them, I can relax and be myself. They get my dry humor. They laugh at my jokes. They listen, truly listen, when I say something important. Our being together each day transforms us.

Starting in first grade, most of our class remained together across the course of our education at Hartville Christian School. Myrrl joined us in the seventh grade. But rather than being the enemy, he became one of us.

And eventually, through the force of his moral authority, he led us — in the best sense of the word.

Maybe it was because Myrrl was young and naive. Maybe it was because he recognized and affirmed the talent found within my classmates. Maybe it was because so many of my peers loved sports as much as he did.

Who knows?

It’s like trying to explain why you fell in love. You can’t. From the first day he taught us that summer in Vacation Bible School just before our seventh-grade year, we worshipped Myrrl. By our senior year, we all claimed we were going to make something of our lives — thanks to Myrrl’s influence.

We bluntly embraced the impact he was having on us.

Across our high school English classes, Myrrl introduced us to great thinkers of Christianity like GK Chesterton, CS Lewis, and J.R.R. Tolkien. We didn’t care that these were the authors he was being taught at Malone College. As he lectured and shared about his own struggles with the exclusivity of our culture, my own beliefs melded with his.

For the first time, it began to dawn on me that perhaps other people outside of our church were also Christians. But the power of one’s childhood culture is vast. It is striking to realize that even with his encouragement, it took four years of college, and a year abroad with Rotary in London before I myself had the courage to leave.

Our senior class trip to Boston was memorable. For example, Myrrl loved professional sports, and he was impatient with the rules of the church. So when some of the boys asked to attend a Red Sox game — an absolute no-no within our church – he agreed to take them.

He knew he’d be leaving our community soon.

Three of us boys — either because we were afraid of what our parents would say, or because we really did believe we should follow the rules of the church, or because (in my case) I didn’t really care about professional baseball — stayed behind, along with the four girls.

The trip might well have turned me toward a history major in college. I had read the novel Johnny Tremain in middle school, and that week, walking the streets of Boston and seeing all the famous places where America was formed, I felt giddy. The experience seemed like an Outlander’s journey back through time.

By the end of that trip, if Myrrl had announced he was the Messiah, and we should follow him, he probably would’ve gotten at least 12 of us to go along.

But he didn’t, and so we graduated.

Some of us left, but most of us stayed in the area. We did construction work. Almost all of us became parents. Many of us stayed within the realm of Mennonite culture — although we rejected its most conservative traditions.

But at each class reunion — our 10th, our 20th, and now this our 38th — those who attended talked about Myrrl’s lasting impact upon us. We were his favorite class — and damn proud of it.

Since the reunion, I haven’t been able to quit thinking about Myrrl’s apology.

It finally dawned on me why I wasn’t shocked when I heard it. Why — as I listened to him — his speech patterns, his tone of voice, and even his words seemed familiar.

I had heard them before.

This was still the teacher who opened up to us, who showed his vulnerability. This was the teacher who made us fall in love with him because of his ability to be authentic and real — decades before being authentic and real became a thing.

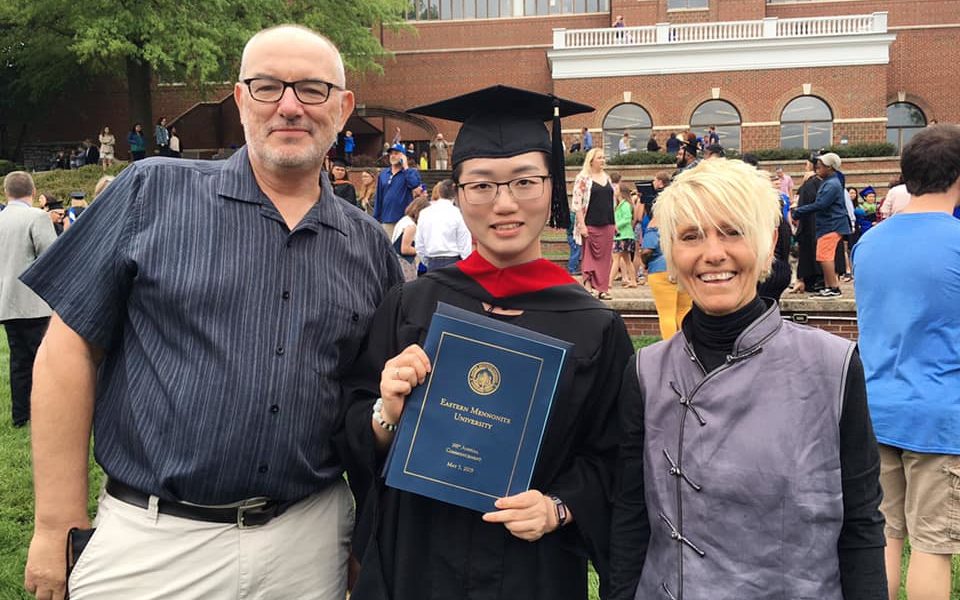

This was the teacher I formally called out as being one of my Soul Teachers. This was the teacher who not only talked about giving your life meaning, but has also helped hundreds of English teachers do exactly that by leaving the comfort of Western culture to experience difficult, challenging classrooms in China. This was the teacher who helped these educators become more tolerant, open, and global.

I remember my own struggle over the past year, encouraged by my supervisor to stand at the classroom door at the beginning of the period in order to address each of them by name. I remember recognizing it was what Myrrl had done for our class.

He truly saw each of us as an individual.

For six years, he had stuck with us — putting off his growing need to leave our culture — in order to play basketball with bookworms. In order to struggle openly in his search for a meaningful life. In order to share himself with a group of stubborn kids who needed to be given a glimpse of how life could have meaning.

Although Myrrl was a private person who didn’t open up easily, he made and owned his mistakes, he got to know us as human beings, and he let us see that teachers too are human.

The resulting relationship changed our lives.

Years later, after I had left the Mennonite church and made my way in the world, I discovered that my teacher’s resignation as principal — followed by his departure from our church community (to go to China as a missionary under the auspices of a “liberal” Mennonite organization) — was viewed as proof positive that Myrrl had been a bad influence on all of us.

Our class was a failure as far as our community was concerned, I was told. As was our teacher. This suspicion hardened into fact when during the next decade, almost every one of my classmates fled the conservative Mennonite culture.

Including myself.

When those whispers reached my class, we were infuriated.

We saw things differently.

We knew Myrrl was the only reason all of us had survived adolescence.

So now at this reunion, as I watched Myrrl speak, and apologize, and break down in tears over a high school chum who had recently passed, and tell us what it was really like to teach while you were fighting to earn your B.A. — I saw the same person I had grown to love as a high school student.

I also saw a master teacher, a man who had grown and matured into someone who helped Eastern and Western worlds connect.

Of course, I also remember my other teachers, especially the one who enjoyed wielding a two-inch-thick piece of wood riddled with tiny holes— and who used it ruthlessly on a helpless child in an attempt to force that child to submit to his God-given authority.

That’s when it finally hit me.

Perhaps the wrong teacher apologized.

Leave a Reply