IT IS HARD to imagine Mr. Dale King without talking about his voice. Rich, rolling, booming — a deep baritone marvel. No one who knew him could forget it. His closest friends, his students who held him in awe, even his peppery daughter, all jokingly called it “the Voice of God.”

My first memory of him comes from a darkened assembly, held in the Malone College Student Center, a simple meeting place created from an honest-to-goodness barn. The ancient beams brought to mind the simplicity of the school’s Quaker roots.

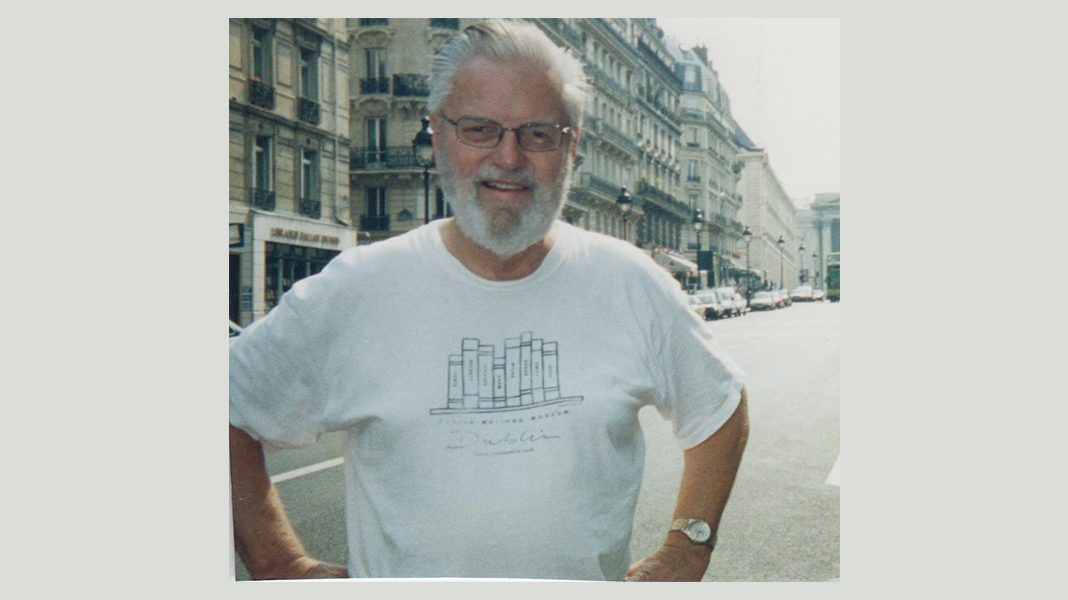

It was lit that night by spotlights. Beneath a crossbeam stood Mr. King, stalwart and severe, silver hair and beard gleaming against the darkness. Amid the choir pieces and solos, he narrated poetry selections, biblical passages, and his own luxurious prose.

His voice was vigorous, beautiful, tinged with the golden syllables of the deep South.

I wasn’t yet a student of Mr. King’s — I merely knew students who revered him and told me stories — but by the time I left that sacred space, I wanted to be.

In fact, it’s not a stretch to say I attended Malone just to take his classes.

SEVERAL YEARS LATER, I had become Mr. King’s student. By then, I had spent a year of voluntary service in Phoenix teaching in a one-room school house. I knew I loved the craft of teaching.

I wanted to teach English for the rest of my life.

So I enrolled at Malone College as a freshman. I signed up for Mr. King’s sophomore-level, Introduction to Literature course. During classes our professor strolled about, reciting poetry, asking questions, striking with his well-groomed beard and thick hair, each class a performance by a movie star.

But I lacked confidence in my command of language. So I also signed up for a basic-level grammar course, what teachers slightingly refer to as Bonehead English.

Grammar for Dummies.

Every afternoon, I sat in a packed classroom, surrounded by surly students who had scored badly on their English ACT. They resented the dutiful adjunct who drilled us in the mechanics of sentence structure. They hated having to participate.

They just wanted to pass the damn course.

One afternoon, I awakened from a doze to see my distinguished professor stroll past the door. A moment dragged past. Suddenly, he reappeared, walking backwards … and yes, gazing at me.

Astonished.

I tried to hide, hunching down, but even there I could hear his muted voice.

“What’s Denlinger doing in there?”

How could I tell him that although my ACT scores had easily placed me in his advanced class, I knew my grammar skills were subpar?

Spelling, too.

My first essay in that class was a blue-ribbon prizewinner. In pompous tones, I revealed the nature of my part-time job — teaching English at a local parochial school.

How many college students do that?

When my teacher returned the paper, I glanced at my grade. My heart plummeted. I flipped through it. Beside my description of my teaching responsibilities, she had splashed a dazzling question mark in bright red ink.

I had misspelled the word grammar. With an e.

Now, with Mr. King just outside, I tried to pretend I was invisible. Tried not to notice my grammar instructor’s curious glance. Tried to entreat her telepathically not to reveal my imbecility to Mr. King. And prayed he’d go away.

He did.

Then cheerfully called me out during my next class with him.

“Steven, what are you doing in Pam’s grammar class?”

The entire class turned in unison to eye me – the impostor in their midst.

Blushing, I explained my fears about writing, my meager grammar, my desire to master punctuation.

In the wake of my confession, to my surprise, he offered only respect.

“Less for me to teach you, young man,” he rumbled.

AT MALONE, MR. King was a popular topic among students. I kept my ears open. They wondered why he hadn’t gotten his doctorate, marveled over his astonishing vocabulary, and murmured that he’d once been a Baptist minister in the South.

During his thought-provoking lessons, Mr. King sometimes talked about his family. He talked about the way he and his wife had raised their daughter, about the trips to Europe they’d taken, usually as part of a school event.

It was clear the King family had a lifestyle devoted to art, literature, and God — and not necessarily in that order.

Mr. King even talked about their old Victorian home in downtown Canton. I soon deduced it was located on the wrong side of the tracks. During one of his evening classes, he told us with dramatic effect about a trespasser he’d confronted.

“As I strolled around the corner of our house, what should I see but a woman, dressed in tattered garb, using the front of my lawn as” — he paused, almost stuttering in his visceral horror — “as a sort of outhouse.”

“I said, ‘Madam, whatever are you doing? This is highly irregular.’”

The class roared with laughter.

But the hidden truth did not escape me. Even in this extreme circumstance, he’d addressed the wrongdoer with grace.

MR. KING WAS soon assigned to me as my faculty adviser. I quickly found that he took that role seriously — both its academic and spiritual aspects. He had taught several students from our Amish-Mennonite church.

He understood the choices I was facing.

More than once, I’d received a brief note from him, encouraging me to come talk to him about course selections I was making. His writing, even a simple note, was almost poetic — the warm Southern kindness that suffused his character and breeding infusing even the most pedestrian of epistles.

I found he respected people who stood their ground, who allowed principles to guide their actions.

Once, he assigned us to read a series of essays into a tape recorder. Prose by G.K. Chesterton, Winston Churchill, George Orwell. When we got to George Bernard Shaw, I found myself uncomfortable with his language, with an analogy I considered sacrilegious — Shaw stating he preferred to become “his own holy ghost.”

Mr. King graciously listened to my concerns.

“You may decline to read that speech,” he told me gravely, “but I can’t give you credit for the assignment.”

“I’ll take the F,” I told him painfully.

To my shock, he smiled at me.

As I left the room, I realized I had passed another of his tests. One that carried far more weight.

ALTHOUGH BORN IN Flint, Michigan, Mr. King had moved to the South to attend Bob Jones University in Greenville, South Carolina. After he matriculated, he was hired to teach there.

Mr. King had embraced the South’s most romantic and gentlemanly qualities. The Almighty to him was powerful and masculine, and in Mr. King’s mind, God expected men to behave in the same manner.

Like all Southerners, Mr. King believed a gentleman’s first duty was to defend the honor of a woman. In his mind, feminist critics aimed to annihilate the core essentials of civilized society. Feminism was a liberal sellout. It also ran counter to the Apostle Paul’s teaching that the husband should be the head of the house.

He believed this biblical principle with his whole heart.

But Mr. King didn’t match the stereotype of a typical Southern patriarch. Watching him with his wife, I saw he respected her as an equal, and she spoke her mind quite freely. This was confirmed to me as I listened to his daughter Meredith — we became friends on a college Shakespeare trip he led to Stratford, Ontario — and she told me she felt very free to speak her mind in their home.

No patriarchal oppression there.

“My father always told me, ‘You can say whatever you want, as long as you say it respectfully,’” Meredith informed me. “When I said something snarky or flippant as a child, I would hear his voice, even in the next room. ‘Tone, Meredith, tone.’”

I ONCE ASKED Dale — during a break in one of our many courses together — why he chose to leave the ministry.

It was a summer course, three evenings a week, when I stole away from my grueling construction job to sit through a four-hour session which never seemed long to me. Dale knew how to tell a story, and I was fascinated by him — and like all students who love their teachers, I wanted to find out what lies beneath their mystery.

His response is engraved in my memory.

I knew by then Dale had taught at Bob Jones University — a fundamentalist school in the deep South — but had left during a conflict with the administration to come to Malone. He had briefly shepherded a non-denominational congregation in a nearby town. Then he had abandoned the pulpit.

Now I waited for Dale’s response.

“It was a complicated decision,” he said finally. Around us his students gathered, drawn into our conversation.

His smile twisted oddly as he spoke, probably trying to hold in all the pain.

“I just couldn’t look someone in the eye who had gone through a divorce and say, “Welcome to celibacy for the rest of your life.”

That’s all he said. What else could he say?

Only recently did I truly understand his answer.

My mentor wasn’t a fundamentalist, obsessed with following the literal words of Scripture, even when that literalism makes Truth disappear.

Dale was orthodox, a perspective which promotes a far more merciful faith, one that recognizes that all of us have fallen — but that Justice must have as its counterpart Mercy.

AFTER COLLEGE, I kept in touch with Dale. I could always count on an enthusiastic response when I called to say I was coming up from Steubenville to see my family. He’d give me a sacrosanct slot on his personal calendar.

We watched movies together; that was our thing. I’d meet him at the theatre, and he’d come hustling up, hand outstretched for a firm handshake.

Dale always maintained an appropriate reserve. He’d sit beside me, arms crossed, following the action with focus and intensity, occasionally grunting when the story took a powerful turn, or sighing his satisfaction when a character made a particular insight.

Afterwards, we’d meet at a vintage ice cream parlor in Canton — Taggarts, a popular hangout from my college days. It featured old fashioned “Wimpy” hamburgers and fries, and its famous ice cream contained 14% butterfat.

We drank bottomless cups of coffee in the high-backed wooden booth, and slurped down their most popular sundae, The Bittner, a blend of vanilla ice cream and homemade chocolate syrup, with salted, roasted pecans falling over the sides, topped with a large dollop of whip cream.

During these golden years, Dale continued to share his stories. He offered advice when asked, wisdom I needed to survive in a modern lifestyle rejected by my family.

I was well aware our conversations were like those of father and son. Not only did we plumb the depths of Dale’s faith. He also inspired my own vocation.

I saw the deep-settled joy that permeated his teaching memories. I saw the respect that infused his relationships with colleagues. I saw the kindness he exhibited toward others by the moments he chose to recall.

THAT ERA IN my life — regular outings for movies, coffee, conversation — ended in 1996 when Dale and his wife moved to Florida. Their daughter had married, Dale had retired, and Carlene had found a job teaching English at The Geneva School near Orlando.

He didn’t make a very good retiree. Still in love with teaching, Dale was quickly drawn into teaching junior-high history at his wife’s new school. Eventually, they promoted him to high school English.

It was there I managed to pay Dale a visit.

I knew how much I’d missed him when I saw him at the airport. His broad face creased in a smile, that generous Southern welcome, his sheer delight in seeing an old friend.

Driving to his house, I savored once again the beauty of his voice, the gleam in his eye as he worked into our conversation a favorite line of poetry, the pauses as he searched for just the right word, his delight when I quoted back to him a favorite verse.

I remember our outing to the beach. He didn’t swim, just sat on the sand in his white tee shirt and blue Bermuda shorts, face placid against the bright sunlight and blue-green water. He was reading George Herbert.

Years before, he had confided in me that he had chosen not to get a Ph.D simply because he read so slowly. He loved poetry because it didn’t take as long to read.

I thought about the close reading skills I had gained from him, his ability to mesmerize a class by reading through a poem, his willingness to spend an entire class period working through its elements, deconstructing its magic.

That weekend in Orlando was a brief flash in the sea of golden memories that was my time with Dale.

Until we arrived at the airport for my return flight.

This was the pre-9/ll world, so Dale and Carlene accompanied me through check-in to the gate. Although the line wasn’t crowded, I must have stepped into the path of the young African-American man coming up behind us without noticing him.

I do that sometimes when I’m preoccupied. Everyone who knows me has seen it happen. But this man didn’t know me. He took it as a slight.

He confronted me. Enraged.

“Get the hell out of my way!” he snapped. “I was here first.”

I backed off, but Dale wasn’t about to let me be insulted. He stepped forward, staunchly defending me.

“Boy,” he thundered, in the rolling rumble of the South. “Who do you think you are anyway?”

I stood frozen, shocked at the racism threading through his words. Beside him, Carlene looked away, somber. My rude assailant shot my teacher a look of hatred.

Dale’s face had turned grim, confrontational. His chest pushed forward. Suddenly the line shuffled forward, and my opponent seemed to wither, then turned away.

After I checked my bags, the three of us walked toward the gate, Dale and Carlene on either side, warm and affectionate once more.

But when Carlene hugged me, and Dale shook my hand goodbye, I found it hard to meet his eyes. I had withdrawn, unable to process what I’d just seen. A man I considered noble had just ripped off his mask and revealed something … not so noble.

In the weeks that followed, I struggled to give Dale the same degree of empathy he had always offered me. Perhaps Dale’s anger had been a response to the man’s rudeness, rather than a racist response. I knew in his mind, rudeness by anyone was unacceptable. As his daughter recently told me, “He could get downright feisty about rudeness.”

Eventually, I got through it.

After all, he had been defending me, his words stripped of politeness by his anger at a stranger who dared disrespect a dear friend. His words had been spoken out of love for me, someone he treated like a son.

Today, when I weigh his actions with the scales he applied to others — a life of justice guided by mercy — his character stands undiminished.

Perhaps it was the pain of a son whose father had just revealed that he is, indeed, human.

OUR LAST PHONE conversation occurred while I was on my way to work, my Subaru swaying on a moving ferry, jostling crowds threading through the cars, the boat churning toward the dock. It was the fall of 2011, and I was living in Seattle with my fiance.

Dale and Carlene were still living in Florida, but his health was beginning to decline. They were thinking about moving back to Ohio so they could be close to their daughter and son-in-law. Meredith had taken her mother’s place as senior English teacher and department chair at Cuyahoga Valley Christian Academy where her mother had once taught.

I was hesitant to call Dale — but it had been awhile, and I needed to hear his voice. I wanted to tell him about my engagement to Laura.

I knew he wouldn’t approve of our decision to live together. But to my surprise he was understanding.

“So you plan to get married?” he rumbled in my ear.

“We do. In June 2012. We’re living together, but as far as I’m concerned, we’re already married.”

Which was true. I was too conservative to move in with anyone without that certainty.

I heard his grunt of approval.

“Well, I’m glad to hear that you’re going to do things properly,” he said, his pride in me generous and unreserved.

It was our last conversation. For most, it wouldn’t quite constitute a blessing. But for me, it was enough.

WHEN DALE PASSED in March 2014, I was in Seattle, unable to attend his funeral in Ohio. But I endured my own private grief as I read what his daughter Meredith wrote about the process of seeing her father into the ground.

I was moved tremendously by a story she told in her eulogy, an image captured from her mother during the weeks following her father’s death.

“Soon after I married your father, we were at a picnic for the children of our church, and someone got into a bee’s nest. I just grabbed the nearest kid and ran, and others were doing the same — but when I looked back, there was your father.

“He was standing over the nest,” Carlene recalled, “arms waving to draw the bees, letting himself get stung multiple times, until everyone else could get safely away.”

That image symbolized everything Dale meant to me.

DALE WAS NO fundamentalist although, like me, he began there.

Ultimately, he chose orthodoxy guided by compassion. Perhaps this is why I love him so, the way he allowed

Mercy to guide him, the true humility that permitted him to exercise one of the greatest minds I’ve ever known — yet humbly admit he didn’t have the fortitude to earn a Ph.D.

As my teacher and later mentor, he guided my intellectual and moral growth, offering me much-needed advice even when I didn’t want to hear it. He taught me what it meant to be a Christian in a culture that swung and shifted around me as I traveled and grew.

He shepherded me through the doubtful years when I questioned my faith — showing me by his own example how to stand strong against an abusive, patriarchal religion.

In so many ways, Dale played the role of fearless beekeeper for me, too.

Leave a Reply