I WAS STRUGGLING with my decision to leave my Amish-Mennonite world when I first discovered the author Chaim Potok. In the audio/visual section of the Stark County District Library, I spied what would become my favorite novel.

My Name Is Asher Lev.

Moments later, shivering in the frigid Ohio air, I huddled over the heater of my Ford Escort. With trembling fingers, I jammed the first cassette of the book into the deck.

I hit PLAY.

The warm baritone voice of the narrator filled the speakers.

My name is Asher Lev, the Asher Lev, about whom you have read in newspapers and magazines, about whom you talk so much at your dinner affairs and cocktail parties, the notorious and legendary Lev of the Brooklyn Crucifixion.

I am an observant Jew. Yes, of course, observant Jews do not paint crucifixions. As a matter of fact, observant Jews do not paint at all—in the way that I am painting. So strong words are being written and spoken about me, myths are being generated: I am a traitor, an apostate, a self-hater, an inflictor of shame upon my family, my friends, my people; also, I am a mocker of ideas sacred to Christians, a blasphemous manipulator of modes and forms revered by Gentiles for two thousand years.

Well, I am none of those things.

He had me at “My name.”

It was January 1987. I was a junior in college. That fall, I knew, a Rotary Foundation Scholarship would take me to London, England — far away from my hometown in Hartville, Ohio. I suspected I would be leaving for good.

How do you leave a community like mine, I thought? All my relatives belong to it. All of my boyhood friends. Everyone I truly trust.

I knew people who left. Friends who had grown up within my insular community — and turned their backs on it.

They were bound for an eternal hell of fire and brimstone.

I had condemned these poor souls, publicly. I had spoken dismissively of their heretical faith.

Now — if I left — I would face the same fate.

I tried to convince myself that with me, things would be different. I would just leave my culture. I would just leave the peculiarity of my home community. I would just leave the things behind that were unnecessary for salvation.

My faith would remain firm.

How could I know how difficult it would be to extricate the precious chalice of my faith from the clawing tentacles of my subculture?

IT TOOK POTOK to teach me how.

It was he who first showed me the daunting nature of the challenge. I still feel the sobs that welled up in me, unexplainable, as I listened to Asher reach the climax of his tale.

I remember the Rebbe’s long burning gaze and the silence that filled the space between us. He had read everything. He had followed the papers and the magazines. He understood everything. He sat behind the desk, gazing at me out of dark sad eyes. The brim of his ordinary hat threw a shadow across his forehead …

Then he said, “I will ask you not to continue living here, Asher Lev. I will ask you to go away.

I felt a cold trembling inside me.

“You are too close here to the people you love. You are hurting them and making them angry. They are good people. They do not understand you. It is not good for you to remain here.”

I said nothing.

I think it was then, driving home, tears rolling down my cheeks as I confronted the stark choice I had to make, that I decided to leave.

Although I couldn’t understand why I felt the burning need to leave, Potok’s autobiographical novel lit up the path ahead of me like a prolonged flash of lightning.S

I saw, briefly, the wracking pain ahead of me. I saw, briefly, the myriad friendships I would abandon. I saw, briefly, as the light disappeared, the long dark night of the soul.

But I also glimpsed the freedom I craved as an artist.

In the years to follow, I would lose an entire network of friends and family — first disappearing in waves, then dribbling away, one by one. At first, I fought to keep those friendships alive. But ultimately, I saw our interests and language and spiritual connections wither up and blow away like tumbleweeds, disappearing across the horizon of my life.

IN HIS NOVEL My Name Is Asher Lev, Potok offered me the only emotional blueprint I could find to leave my community and keep my faith.

Asher left his community because they found him threatening. Their faith had no room for his questions. The images he created — nudes, violence, blasphemy— struck at the foundations of literalism they fiercely believed, and thus destroyed their vision of God.

They could not see God within the questions he raised. All they could see in his work was the Sitra Achara, “the realm of evil.”

Asher had to go.

My experience, although not as extreme, was similar.

I too had to leave in order to portray honestly my experience. I too had to leave in order to find a lens through which I could view God. I too had to leave in order to find my voice as an artist.

But only Potok was able to sketch for me the way I saw myself — my dreams and nightmares, the questions and answers I found, the complex push and pull I felt as I contemplated leaving a community I loved passionately and hated fervently.

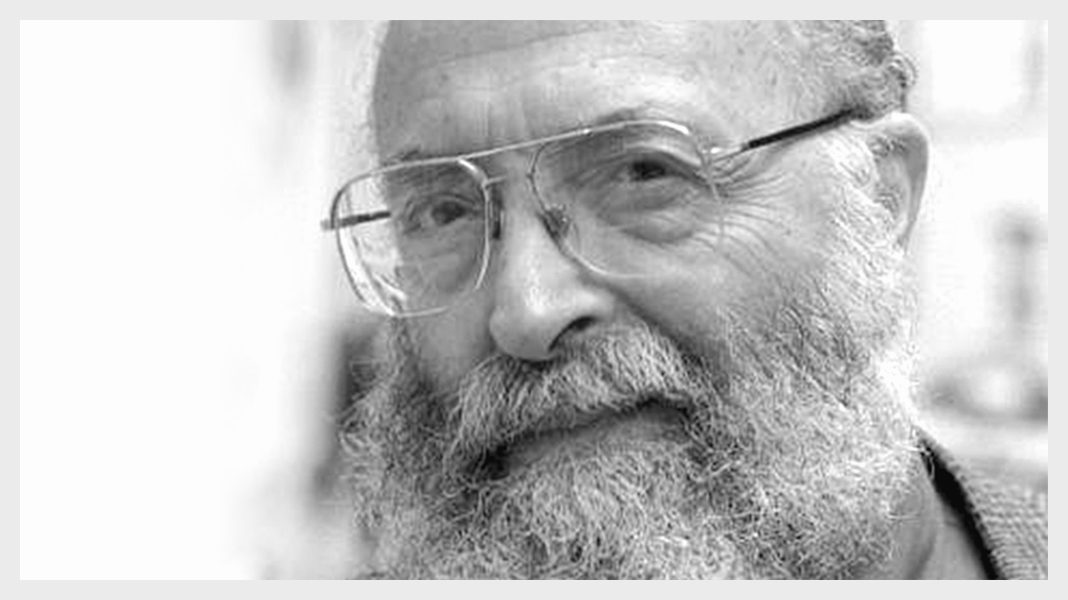

When Potok passed in 2002, The New York Times said this:

“Mr. Potok’s heroes, mostly adolescents on the brink of manhood, feel both sustained and, increasingly, suffocated by their traditional communities. Though they never consider abandoning Judaism, they agonize over whether they dare seek lives in the larger world, knowing full well that if they do, they will be branded apostates.”

I listened to Asher Lev’s journey into the world, awed by Potok’s ability to describe me and my compatriots — those who would eventually follow me out of the Amish-Mennonite world.

And eventually, it was the wisdom I discovered in Asher Lev — articulated in a speech he gave not long before his death in 2002 — that propelled my own memoir over the finish line.

“[A fundamentalist community] . . . by definition is both joyous and oppressive simultaneously,’’ Mr. Potok said in an unpublished 1992 interview. ‘’Joyous in the sense of knowing you belong to some cohesive community that will care for you; in whose celebrations you can participate fully; and who will help you mourn if you need a support group in time of personal tragedy. And repressive because it sets boundaries, and if you step outside the boundaries, the whole community lets you know.’’

Thanks to Potok, I realized his central truth: the fundamentalist impulses that guided my childhood community were not unique to the Amish-Mennonites.

I too had to go.

CRITICS ARGUE The Chosen is Potok’s finest novel. It’s certainly his most approachable story, one that has been taught in many high schools. But the critics are wrong.

To be clear, my metric is different. I’m not approaching the book as a literary critic. I’m responding to it as someone who sees myself within the main character. In my darkest moments, after I left, I gained spiritual strength from his experience.

I found meaning within Asher’s suffering.

Thus, to me, Asher Lev — a painter who was not permitted to express his gift within his community — is the greatest protagonist Potok ever created.

The questions he raised in his paintings, his refusal to let the fundamentalism of his people stifle what he had to say, his willingness to risk everything in order to fulfill what The Gift demanded — all of this made him a hero that any fundamentalist émigré could emulate.

In my mind, Asher Lev stands alone. This character — one whom Potok admitted is highly autobiographical — showed me the way out.

POTOK HELPED ME see the similarities between the passionate beliefs I saw in my childhood world, and those I saw in other insular communities.

And in this way, he was my greatest spiritual guide.

He performed this feat by approaching his questions honestly. He never hesitated to consider the possibility that he could be wrong. He confronted his darkest moments within his art, never hesitating to display them truthfully on the page.

In spite of this — or perhaps because of this — the foundation of his faith never shifted.

In a speech he gave not long before his death, “On Being Proud of Uniqueness,” Potok spoke of the way he saw “a dramatic confrontation of cultures” one afternoon while he was strolling through a Japanese market in Tokyo:

“I came into a Shinto shrine where an old man with a long, white beard was praying to an idol. Dressed in a tattered grayish suit, unadorned, with a book in his hands, swaying back and forth he reminded me of the old Jews in the synagogue I used to pray in when I was a child. The intensity of the prayers in that synagogue was no more intense than that of this old man as he prayed to the idol.

Potok’s comparison of the Jewish and Shinto experience of faith reminds me of a similar experience I had when I was in London, not nine months out of my Amish-Mennonite culture.

Standing in the Richmond College Common Room in April 1989, just days before I returned home, I was introduced by a classmate to a young Egyptian woman dressed in a red mini-skirt. We connected quickly.

At first she teased me. But then our conversation turned quickly serious.

She told me she would soon return home to Egypt, don the Muslim burqa, and marry a Muslim man her father had chosen for her.

“My father is a fundamentalist, too,” she told me after hearing about my father’s beliefs. “Only he’s Muslim — not Mennonite.”

ANOTHER MOMENT OCCURRED in Los Angeles when I became romantically involved with a woman who was an avowed atheist. For months, I ignored our differences, thinking that our mutual respect for each other would overcome all.

But it was not to be.

One afternoon, I was defending the way many evangelicals reject evolution. My partner suddenly exploded in anger, pounding on my chest. Her fists were surprisingly painful.

“You’re so intelligent and bright,” she said, tears of anger and frustration in her voice. “How can you believe that shit? The scientific evidence is so strong.”

Later, having dinner with some friends on my apartment patio, I shared that conflict with my friends. One of them was a story analyst at a major television studio.

“Oh,” she said. “Your girlfriend is a fundamentalist Atheist.”

My jaw dropped.

“What’s that?”

My friend looked at me in surprise.

“I thought that would be obvious,” she said. “She’s just like any other fundamentalist. She believes her brand of belief is the only one anyone can believe … or they’re not intelligent.”

THIS WAS A turning point for me, a time when I hit the wall, a moment when I realized that although I had rejected the culture of my birth, I had not rejected its God.

And so I returned to the faith of my childhood — its emphasis on salvation through the community, a faith that expresses itself in works of servant leadership, a gentle tolerance for those who disagree, a generosity that opens itself to The Stranger.

I did not, however, return to the fundamentalism I originally abandoned.

Thanks to Potok, I learned to distinguish between a faith that is confident and true and a faith that is fearful and dark. He still dominates the emotional landscape of my reading.

He was a great Soul Teacher.

SEVERAL YEARS AFTER leaving my community, I remember running into one of my boyhood compatriots at a Mennonite church service. I was a musical performer that morning. He had taken my place as a teacher at a nearby parochial school where I had spent an unhappy year.

“How is teaching going?” I asked.

He sighed, telling me about how difficult it was to maintain discipline. I nodded politely, then started to turn away. Suddenly, I felt his hand on my sleeve.

“I think they made a mistake. Letting you go. The Church needs artists like you.”

My eyes misted over.

“It’s all right. I’m happy where I am now.”

The crowd around me jolted toward the exits. My friend was moving against the flow. I turned with the crowd, but then stopped, glancing back.

He had disappeared out the back door, and I didn’t see him again.

Leave a Reply