IT’S HARD TO admit you’re wrong.

It’s especially difficult when the person criticizing you — someone you’re sure knows far less than you — doesn’t merit your respect.

Like an annoying high school student.

Yet some of my most powerful lessons — and these were moments when my life transformed dramatically — have taken place under the unsparing gaze of students.

In particular, Bethany and Sharon.

IT WAS AT The Archer School for Girls when I was most decisively schooled about how to treat my students.

As a veteran teacher, I had my stage patter well-tuned. I had the fine art of the sarcastic comeback down cold. And the kids loved it. My smart-ass remarks never failed to get a laugh.

Using sarcasm even worked as a discipline strategy. There’s no better way to really let a kid know how you feel about them.

Like the student who comes late to class.

“Did all four tires blow out this time, Jill? Oh wait, you gave that excuse last time.”

Or the student who turns in an assignment late.

“Let me guess. It was your pet llama this time.”

Or the student who can’t quit talking.

“Oh, don’t mind me. I got nothing better to do with my time than listen to your brilliant insights on … shopping!”

I remember one student writing me an evaluation that noted: “I would enjoy learning from you a lot more if you weren’t so damn cocky.”

I thought that comment was especially funny.

Truly, I had missed my calling. I should have been a comedian.

THEN CAME ONE of the most painful student-teacher conferences I’ve ever had. My department chair dropped by my room. There were some issues a student needed to share with me, I was told, vaguely.

Perhaps during my free period?

When I arrived at the conference room, I realized the student was one I had worked with for years. She was now a senior. I’ll call her Bethany.

As I took my place, I realized the room was becoming quite full. Bethany’s mother. My department chair. One of the counselors. The assistant headmistress.

Bethany’s counselor opened the conversation.

“Mr. Denlinger, Bethany has some concerns about your class.”

I looked at my student, confused.

“But you’re doing so well in my class.” It’s true. She was a solid student.

My assistant headmistress gestured. “Don’t be afraid, Bethany. Mr. Denlinger wants to hear. Tell him what you’ve told us.”

My student shifted in her chair, then finally blurted it out.

“You know, Mr. Denlinger, you’re really mean to us in class. Your hurtful comments? They’re just not funny.”

I suddenly remembered making a caustic remark to her in front of the class. I had been rewarded by a burst of laughter. She had reddened, and I had casually apologized, then forgotten the moment.

Clearly, she had not.

“Bethany, I am so sorry,” I said. On the other side of the table, the adults turned their full attention on me. But I saw only my student.

“I really didn’t intend to hurt your feelings,” I said. “I have nothing but respect for you. I’ve known you since your seventh-grade year.”

By now, tears were running down my student’s cheeks. I wasn’t crying, but I wished I could have. My stomach roiled, acid coursing across the lining.

Bethany turned and looked at me.

“I’m okay, Mr. Denlinger,” she said. “I just thought you should know how some of us feel when the entire class laughs at us.”

MARY KARR ARGUES in her book The Art of Memoir that when you tell stories in which you are critical of people, you should almost always make your target yourself.

I think the same holds true for teaching.

After all, when you’re the butt of a joke, everyone else can laugh — and the teller should never laugh at their own jokes anyway.

My experience with Bethany was searing enough that I chose to eliminate sarcasm from my collection of teaching tools.

I suppose I picked up the solution from my father.

More than once, I saw him roll on the floor with laughter at a joke someone told. If I recall correctly, he was the teller, and the butt of the joke was himself.

IF THE ANTITHESIS of caring for students is sarcasm, then compassion and empathy is the basis.

I’ve recently been reading the memoirs of Father Gregory Boyle, a Jesuit priest who has spent his entire career working with gang members, mostly Hispanic and black, in Los Angeles. His definition of compassion is powerful.

“Compassion can only be shared between equals,” argues Fr. Boyle in Tattoos on the Heart. Thus, to help someone you inwardly despise means you don’t offer them compassion, but arrogance. Compassion needs to be a “covenant between equals” to create a place of genuine community.

The best teachers I’ve read state unequivocally that building a safe, caring community within your classroom — a place of “true kinship,” as Fr. Boyle puts it — is the key to learning. This is difficult to do when a teacher sets himself up as the Master.

Innovation, creativity, kindness all require democracy to flourish.

This concept is difficult to grasp. The novice teacher believes that to evaluate a student’s work, he must first prove that his knowledge and skills are superior to the student’s.

Except that’s crap.

I REMEMBER THE first time I realized this.

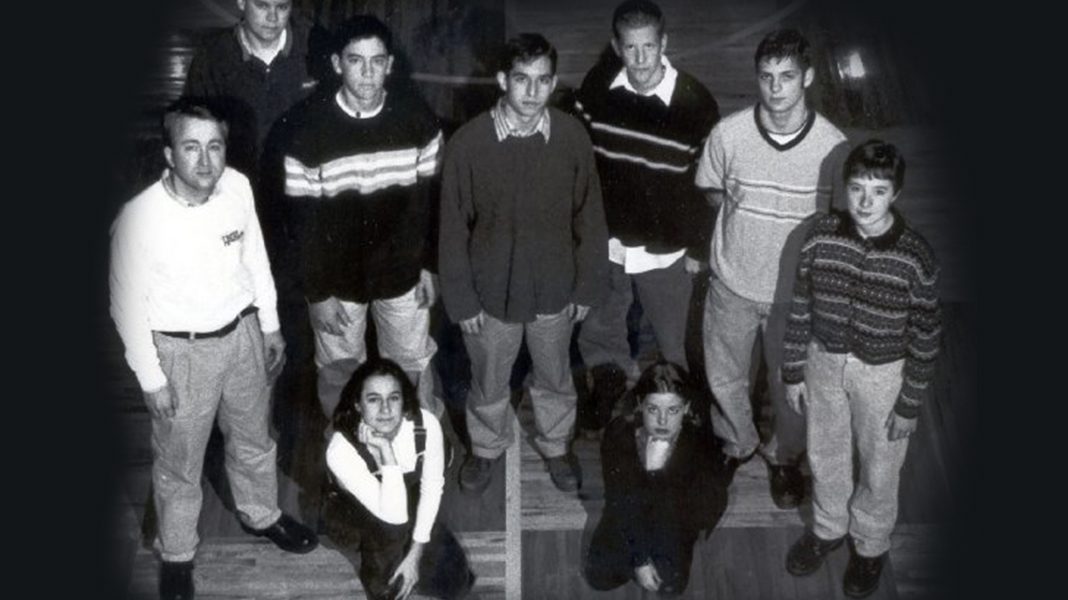

I was teaching at Steubenville Catholic Central at the time, advising the yearbook staff. I didn’t know that much about journalism, especially yearbook journalism, and I just happened to recruit a junior who was ambitious, talented, and intellectually agile.

Her name was Sharon.

Her intellect was razor-sharp. She was five steps ahead of me in discussions. In fact, her entire staff was.

That summer, I drove Sharon and two other editors to a journalism camp at Mount Union College in Alliance, Ohio. It was taught by one of the best journalism teachers I knew.

I attended the same classes as my staff. To my embarrassment, when concepts were taught and then we were released from class to practice them, I found I had missed critical details during the lecture.

More than once, I found my students applying the concepts, and then having to explain things to me.

“Here’s the way it works, Mr. Denlinger,” Sharon said.

I watched as she and her staff unpacked the visual design concept before my eyes.

“If we make this the dominant element, and then wrap these three photos around like this —”

“Oh, yes. And let’s make all of the elements black-and-white except for this small photo over here —”

“Yes, that will make the color photo really pop —”

It suddenly made sense to me.

“Wow. You’re right. I didn’t get that.”

We all looked at each other — teacher and students in the thrall of a brand new discovery.

Wide smiles on the verge of laughter.

Learning disguised as surprise.

Shit-eating grins.

REFLECTING ON THE moment afterward, I realized I was unhappy. I should have been delighted. My students had nailed their lab assignment.

But something felt … off. I had had little to do with what they had learned. It all came together during a conversation with my colleague later that day on the way to lunch.

“What do you do when you realize your students are smarter than you are?”

My mentor glanced at me, surprised. When he realized I was serious, he roared with laughter.

“Oh, Steven,” he said. “Of course they are.”

I stopped on the sidewalk, confused. What was he saying about my intelligence?

Understanding my confusion, he turned and came back to me.

“We don’t teach because we’re smarter than our students,” he told me. “Only a pompous ass believes that.”

By now I was bewildered. My mentor took a moment to let it sink in, and then went on.

“The best teachers learn from their students. Your job is to help them figure things out, not prove you’re the smartest guy in the room.”

My mouth dropped open, but his mind was on other things. He looked toward the cafeteria where we were headed for lunch.

“Come on, I’m hungry.”

THE REASON SHARON and Bethany are my Soul Teachers is because I learned a critical skill from them.

Compassion, respect … it’s the basis for learning. When a teacher is ruled by this principle, the classroom becomes a safe place where students feel motivated to learn.

Treating my students as equals — believing every student has something to teach me — makes me curious, attentive, and respectful.

And it makes my students triumph.

My kind of writing! Great impactful lesson here. I could feel your astonishment as your mentor revealed it to you. Thank you.

Steve, David and I are reading some of your archives. Do you read comments about articles from 2018? in case you do, I love the concepts you explained here. And it explains the difference or growth I see in you. (incidentally, we all need to keep growing in these ways all our lives.. I hope I do!) These principles are the basis for good relationships in general. People love to be around someone who respects them and is compassionate.